Journalism, Libertarianism and the Future

Read/listen to my interview about AI, ChatGPT, and progress on the UNCAVED podcast.

A few weeks ago, I recorded an episode of the UNCAVED podcast, which is hosted by Ashley Kim and produced by Maxwell Wilson, two students at Columbia University whom I met at a Young Voices event held recently in New York City. They work at an alternative publication called The Knickerbocker, which proclaims itself “the home of heterodox news and opinion at Columbia.” (The title of the podcast, fwiw, is an illusion to Plato’s cave.) The episode went live a couple of days ago and I’m happy to share links to it, plus a TOTALLY RUSH UNCORRECTED transcript below.

It’s a fun and wide-ranging conversation, I think, notable mostly for my optimism in our discussion of AI, ChatGPT, and the like. As I get older, I’m not only increasingly upbeat about the future, I’m starting to see recurring motifs and themes in my work at Reason and beyond, and this conversation highlights my belief in short-term and long-term progress with a small p. I’m always very frightened of capital p Progress, which I associate with utopian plans that always end up literally and figuratively grinding up people who refuse to get with the program—or pogrom, as it were.

I keep coming back to the fact that I’m only a generation removed from the ghettoes that my parents grew up in as the children of Irish and Italian immigrants who showed up here in the 1910s. My father was born in 1923, in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of Manhattan, at home and in a building and on a street that no longer exist. My mother was born in 1927 in Waterbury, Connecticut to parents who never learned English and were able to go about their lives speaking only Italian until they died in the 1980s. My grandparents, like most immigrants, came from what could only be called shithole countries and my parents—and aunts and uncles—were very much the sort of “somebody else’s babies” that former Rep. Steve King of Iowa freaked out about a few years ago. The distance from the world in which my parents were raised and the one my children will inherit can’t be measured simply in years. It’s really a different planet, and a vastly better one.

How we got here and how we keep progressing (again, small p) in moral and material ways is in many ways the fundamental question I keep returning to. We live in a far richer, fairer, and inclusive world than a century ago; as the Superabundace guys can tell you, things are looking up for most people around the globe. What drives me nuts more than anything are people who either deny that we have made progress at all or, even worse, discount it as nothing important (there’s a right-wing version of this, articulated by people such as Tucker Carlson and J.D. Vance, and a left-wing version espoused by Bernie Sanders, who ignores massive declines in poverty while assailing stupefying choices in toothpastes and sneakers). On a profound but mostly unacknowledged level, we have created a world in which a vast and growing majority of us are technically middle-class or rich. In other words, we are so far up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs that we are searching for meaning rather than simply trying to eke out a living. There’s a lot to talk about it, but we should start with an acknowledgement of that accomplishment, I think.

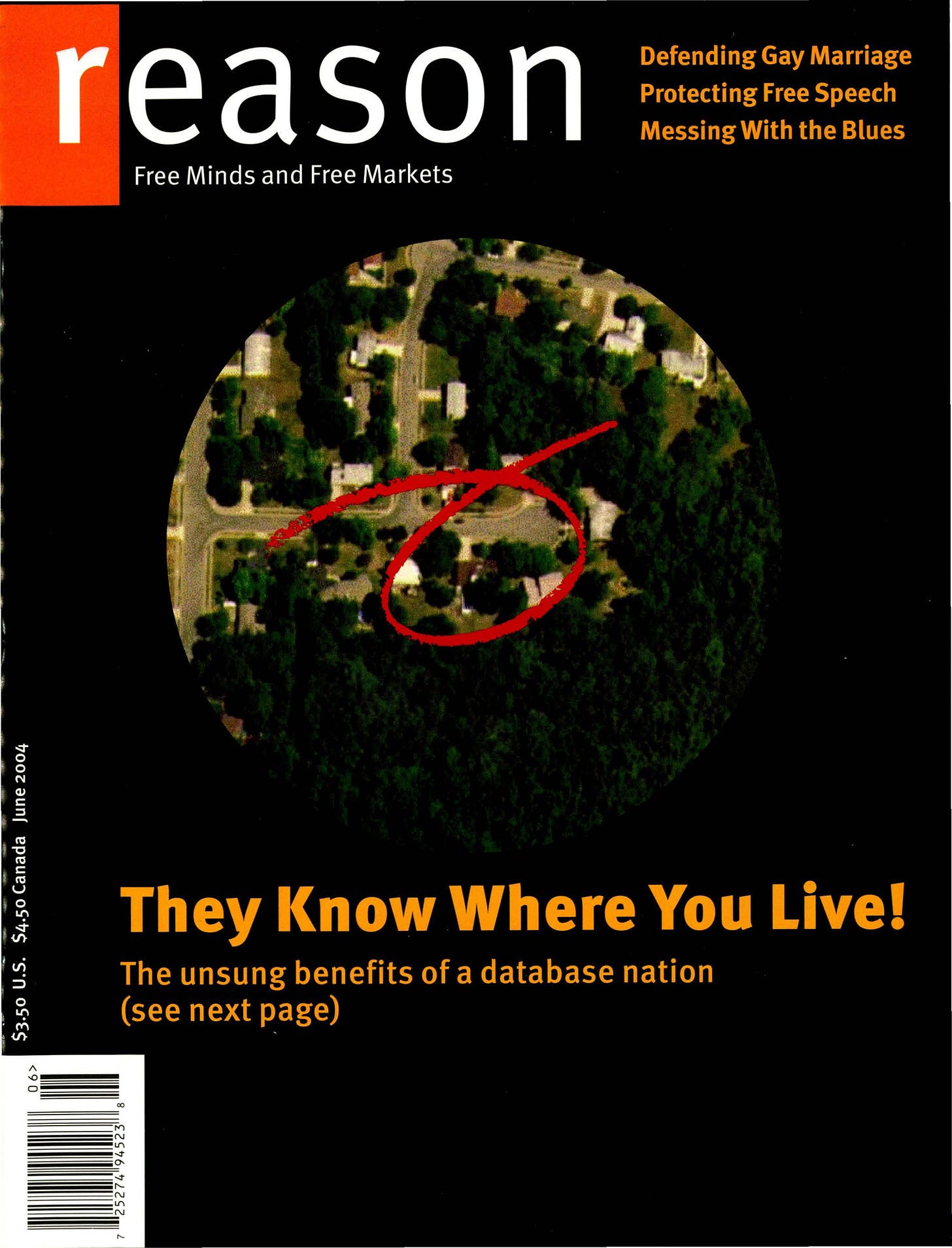

That’s part of what I talk with UNCAVED’s Ashley Kim about, along with a quick history of my time at Reason magazine, especially our June 2004 issue, which made publishing history.

Here’s a snippet from the podcast, cleaned up a bit for readability:

I was born in 1963. My parents were born in the 1920s. They were the children of immigrants and the world my grandparents grew up in—rural farms in Ireland and Italy—still exists. In my grandparents' hometowns, there are the same number of people as there were 500 years ago, a thousand years ago. The world they left still exists, but it's so distant from even what my parents grew up in in America, and then what I grew up in late-20th century America. And I find [that amount of change] energizing, I find it liberating. I find it exciting and innovative and forward-looking.

But I recognize too, a lot of people find that terrifying because it does seem like if nothing lasts forever, you know? How do we know how to live? How do we not go insane with just [indulging] unsated desires or hopping from one thing to another? You see on the right and the left, in the US as well as the rest of the world, you see different responses to this. But they always insist…on controlling people. You have to worship this God. You have to do things this way. You have to pay obeisance to these groups or these traditions, to this state or to thus business, whatever, you know. That impulse is a profound challenge to [a libertarian mindset]. And it's a particularly intense moment for that kind of dialogue right now.

Here’s the podcast itself, as an audio-only YouTube link and on Spotify.

I’m happy to post a VERY ROUGH AND UNCORRECTED AUTOMATICALLY GENERATED RUSH TRANSCRIPT (please check any quotes against the actual audio of the podcast).

Ashley Kim (00:00:22):

Welcome back to the Uncaved podcast. Today we sit down with Nick Gillespie, who is editor at Large at the Libertarian Magazine of Free Minds and Free Markets. He's also the host of the Reason interview with Nick Gillespie and the co-author of the book, the Declaration of Independence, how Libertarian Politics Can Fix What's Wrong With America, A two-time finalist for Digital National Magazine Awards. The Daily Beast named him one of the right's top 25 journalists under his direction Reason won the 2005 Western Publications Association Award for best political magazine. Gillespie's work has appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, the New York Post slate, salon time.com marketplace, and numerous other publications. Without further ado, here's Nick Gillespie.

(00:01:13):

Welcome Nick, and thank you for joining the podcast. We're really excited for this. And you're someone who, and we talked a lot of professors here who have a lot of experience in academia, but you certainly offer a different perspective in the journalism world too, which has its own changing landscape. So, one thing I wanted to ask you about to start it out with, you can talk about a lot of things, but something that I think you did that was very notable that I really liked as a libertarian myself, also someone concerned with the state of journalism is, was it your idea, I believe to put the, put the satellite view people's houses on the magazines that were accustomed to them when they

Nick Gillespie (00:01:47):

Subscribed? Yeah. Back in the, you know, 2004 reason a supporter of the magazine who ran a direct mail business and came to me and he talked about this technology that he had, which was essentially a super fast printer that could individualize covers or content in kind of direct mail like, you know, catalogs and things like that. And he explained it to me and I was like, that's sounds really fucking cool. And then it took a while to figure out, okay, what, what would we want to use that technology for? And what we ended up doing was mass personalizing about 45,000 issues of the magazine. So that individual subscribers, the cover, the inside cover, the back cover, and the inside back cover all had personalized material. And we, you know, the, the big thing was we tied it to a high quality photograph, a satellite photograph of each subscriber's address, and we put their name on the cover cuz we had all this information.

(00:02:51):

And then I wrote an editor's note, and we, we had about four pieces of information that we keyed things off of. So we talked about local congressional races, you know, based on their, their zip codes, their congressional districts, things like that. And we had two advertisements that were also geared to them based on where they live and a couple of d other pieces of demographic information. So and what's most important about that issue actually was the cover story was the subtitle was something like the Upside of Zero Privacy. It was actually a celebration of how massively network databases that were increasingly available to almost anybody had reduced transaction costs. So, you know, one of the, the stats that stayed with me was that it took about a full percentage point off of mortgages, which were aver, like averaging around four or 5%. But by the, the ease with which banks could do credit checks and kind of get more information about prospective borrowers, they were able, you know, they passed on a lot of that savings to the customer. So we were actually celebrating, you know, the loss of kind of privacy on you know, on because of more information being out there. And it's funny, we've talked about it you know, since then, and it's, you know, like, it's probably a little more complicated than we thought.

Ashley Kim (00:04:19):

What made you say it's more complicated

Nick Gillespie (00:04:21):

That we, you know, privacy is one of these issues, which gets talked a lot about. It is always it's, it's always lamented and it's p you know, once it's passed or some version of it has passed. But if there is such a thing as a social construction of reality, privacy is one of those concepts, what it means to be private, what, what privacy means radically changes from almost from year to year. There was, in the early 20th century, there were a couple of Supreme Court cases within you know, a few years of each other. One involving whether or not the police needed law enforcement needed a, a warrant in order to listen in on phone calls. And the Supreme Court decided there is no expectation of privacy on a phone call because most people had party lines. So like anybody, you know, in whole neighborhood, you would pick up the phone and you could hear other people having conversations. And then a few years later they were like, you have an absolute right of privacy, an expectation of privacy, and hence law enforcement needed to get a warrant. So that it, I mean, it just goes to show how quickly what privacy, you know, how we think about it now interesting. It just changes from time to time.

Ashley Kim (00:05:34):

Interesting. Okay. So how do you think, I mean, the, the move that you did privacy is I think, a very interesting, you know, philosophical issue in and of itself, but to what extent do you think it accords at the ethos of Reeds Magazine as you've conceived of it, especially as editor-in-chief?

Nick Gillespie (00:05:47):

I joined reason in 1993 as an assistant editor. I became editor-in-chief of the print magazine in 2000 and stepped down from that, became editor of the video platform. I helped originate that as well as the website from 2008 to 2018. And now I'm an editor at large, but I, you know what, I think that story and that cover, because this was the first time any magazine had mass personalized things, particularly, you know, in the tens of thousands. It, it was a real, you know kind of first. And I'm very proud of that. And, and that I think the marriage of technology and subject matter and kind of delivering something new and different on the cutting edge of what was available then you know, that's very much in the keeping of reason reason was established in 1968. We call ourselves the, the magazine of Free Minds and Free Markets.

(00:06:44):

And since then we've grown into a website and a video platform and a podcast. I wouldn't quite call it an empire because we don't believe in empires we're, you know, because we're libertarians. But we've, you know, got a growing number of podcasts as well as obviously the print magazine. And I think that issue and the way we presented the material, it very much personifies what we're trying to do, which is to look at the various ways in which innovative, interesting things happen when you give people freedom and autonomy and the space to try out new ways of living, to experiment with new types of commerce, to come up with new types of technology. So in a lot of ways, that issue is kind of like the whole package for us, including, you know, the fact that I think looking back we're like, okay, that, you know, that was a great moment then.

(00:07:33):

And now, you know, you know, almost 20 years later we think about privacy in many different types of ways. And I think the big question for all of this stuff is you know, we live in a state, not just where the state or we live in a society, not just where the state surveils us but big corporations do. You know, there's this concept which I think is generally somewhat intellectually incoherent of surveillance capitalism and things like that. But what we, what has happened time and time again, is that we as people opt into or are put into a system where we are offering up more and more bits of information about ourselves or preferences we're giving them to, you know, corporations, we're giving them to our friends, we're giving them to social media networks, et cetera. And so are what our expectations of privacy have radically altered and radically changed.

(00:08:30):

And I think, we'll, we'll be working through these issues for the rest of time. The one place where I think libertarians as a, as a rule and certainly reason comes down to is there should be limits particularly when it comes to the state on when and where, and how they can surveil you or access material that talks about where you have been. I mean, effectively, I don't, oh, here's my phone. You know, we I'm holding up my phone and it's like, you know, we you know, since the first smartphone came out in what, 2007, 2008 or whenever the iPhone came out, we have strapped on surveillance bracelets to our, you know, we carry them willingly and police and a lot of other people could know exactly where you were at a particular given time because of the geo location that is based, you know, that, that cell phones are based around. So like, you know, it's, it's a live issue and it's a changing one.

Ashley Kim (00:09:27):

Oh, certainly. Well, to that extent, I mean, one thing that I really appreciated about your talk that we, that where I saw you a few weeks ago was about the, the role of journalism in a changing tech environment. Now, you talked a lot about, you know, chat, G B T and I think your views on AI are very reasoned from my perspective as someone who's in the computer science engineering world. What do you think the, so I really liked that last article in particular, the, the issue you described brilliant, I think marriage of, you know, journalism, but also very pressing issues about tech that are very, very properly illustrated if you're able to individualize it to every subscriber. Do you think, what's, what do you think something like that would be now? Would it be, I don't know, a chat, G B T A generated a descriptor of every single demographic you'd be sending to? Ah, yeah. That, I don't know. I'm trying to think about

Nick Gillespie (00:10:12):

That. That's, I mean, it's kind of fascinating. A friend of mine who works in kind of AI enabled techno technology startups and he's working on a project now, which, and I'll, I'll get to how this plays in particularly with ai, but it's a type of continuous blood sugar monitor, which you you know, you, you have on your arm and it shows you what your blood sugar and a bunch of other levels in your, in your bloodstream and, and kind of in your metabolism are based on what you're eating, et cetera. And like, it's real-time feedback. And so there's this loop where you can really personalize your blood sugar, like on, you know, on some basic level, you know, you are doing that already because your blood chemistry is yours alone. Even if you're an identical twin, you know, have an identical twin, they'll be a little bit different because of epigenetics, et cetera.

(00:11:06):

But the idea is that you will be personalizing blood sugar levels and other, you know, kind of metabolite metabolic processes for what you need in the moment. If you need to feel a little more energy, if you need to calm down, if you're anxious, et cetera, you'll be able to, you know, really kind of regulate and moderate and kind of intensify the effects that you want based on this marriage of technology and kind of individual autonomy. He has also has talked to me a lot about how we take, you know, personalization, mass personalization and mass individualization. And I think in, in a profound way is the story of modernity. If you go back to the enlightenment, if you go back to the cultural not the cultural revolution, thankfully, the industrial revolution in, in a profound way with the origin of the printing press, you could e you can stretch this in, in kind of obvious ways to the Protestant reformation and a change in how we interpret or, or who gets to interpret what God is and how I read the Bible, or if I read the Bible at all, et cetera.

(00:12:10):

Like, we have been moving as a society certainly in, you know, what used to be called the West. But I think, you know, on a planetary basis towards a more individualized world where it is, you know, seen as good and proper that individuals have more choices have the right and resources to make more choices about their individual lives as they see fit. One of the promises of the internet and of a lot of computer technology was to, you know, really help that out. And in the nineties, I, you know, and again, I started in at reason in nineties after getting a PhD in literary and cultural studies at SUNY Buffalo, where I, I was thinking a lot about this kind of stuff, but what was great about the internet is that it was individualizing our experiences. We, instead of being, you know, subscribing to a magazine or, or a newspaper that put out the same thing for everybody, you could hunt out all different types of sources with with what was then a radically new and, and ease of going out and finding different sources and building your own kind of daily news diet in a way that was much harder to do, you know, just before the internet.

(00:13:22):

And of course, it was easier then than it was, you know, a hundred years ago, or 200 or 500 years ago. But what AI conceivably allows, or rather, the way that the internet became massified where everybody started using it, was the worldwide web, which is based on web sites where you would go around and surf, et cetera. You know, the early big sites on the internet for news were aggregator sites. There were things like the Drudge Report and whatnot, which pulled together lots of different stuff. They helped us, like little guides or docents to what was interesting according to a particular filter. But you could just make your own. This is a long-winded way of saying that I think AI, on a possible level, particularly the way that we engage with all of the information that is out there now, mu, you know, housed on the internet or housed anywhere, is that instead of going to websites and kind of surfing around or waiting for people to send us stuff, we will have AI bots where when you open your computer in the morning, you might say, you know, it, it will tell you based on what you had been reading or what you're obsessed with, what you were binging on Netflix, et cetera.

(00:14:28):

Here's a bunch of stuff that you might find interesting or reminding you of things you started but didn't you know, didn't finish. So in that sense you know, I'm looking forward to a world of individualized kind of interactions with information sources. And I think that translates into a different relationship to news and things like that. The question with all of this kind of stuff is how do you make sure that you are not, you know, and this is, this is the fear of the modern era, going back to Renee Decart you know, in the cogito, are you cre are you thinking for yourself? Are you, or are you being thought of by someone else who is actually controlling your consciousness and whatnot? And I think this is, this was a big fear in the early internet days. You know, would you be fed things that you think are the whole picture, but are actually a limited bit that has become even more intensified that fear that when you go to Facebook, you're being, you know, all sorts of things are being blocked when you're going to Twitter.

(00:15:34):

Algorithms are blocking things, so you don't need to go outside of your bubble and things like that. Those fears have always proven to be overblown, but I think it's a real concern that we should take seriously. And particularly with things like AI or system, you know, any intermediary between you, you know, and, and, and religion and Christian, you know terms, it would be you, you know, you're skeptical of the priest or the preacher of the minister, or the person who is the intermediary between you and God. You know, to secularize that we should always be worried a little bit that the people who come in between us and what we're after, which are good, you know, that's a good thing. I mean, you know, basically what an editor does is makes information better for the people who want it. But, you know, you always wanna make sure that you're checking your you know, that you're, that you're not walling yourself off through the use of intermediaries that become, that present themselves as the limit of everything.

Ashley Kim (00:16:32):

Well, I think you're very wise to describe this view of individualism, especially as it's tracked over time. Sorry, yeah. I'm getting a little stuck. No, I think you're very wise to describe right? How there's tension between the individual and the collective has been, you know, going on quite some time. It's the ethos of the enlightenment something as far back as, I think that's what toque will described as very American too when he came to America. Yeah. And,

Nick Gillespie (00:16:56):

You know, we can stretch it back you know, the, the individual versus the group, the individual versus the family, you know, the family versus the group, et cetera. These are probably, yeah, I mean, these are human stories. You know, a play like Anny B Sophocles Yeah. Is, you know, is about the individual versus the state or society, et cetera. So, like, you know, these and it, and it's worth, it's worth always figur, you know, looking to the past and see how they dealt with it and how they figured, and also, you know, to the present, because no era you know, we're, we're constantly making errors in our judgments and in our conceptions of things. But one of the great things about literature and history is that it allows us to see what mistakes other people made and hopefully learn from them.

Ashley Kim (00:17:39):

Precisely. And I think what you described too is what Marxism got wrong too. The idea, I think Marx, you know, you correct me here cuz you're better at cultural analysis, but Marks got wrong, was assuming that as everyone gets so specialized in their labor, they'll have only their one thing and won't have the ability, I'd have the breadth to, to describe or to understand the rest of the things. But in reality, the fact that, you know, free markets allow for free time and more leisure time, that allows us to have much, much more specialized and much just more individualized explorations into whatever we'd like, seems to be, you know, the greatest rebuttal to the thing, the phenomenon that Marx is trying to describe.

Nick Gillespie (00:18:12):

So let me say, you know, let me give you know, a critique and then a a kind of support Go ahead. Yeah. Marx's thought because but Joseph Shumer, who's an economist who was born in the 19th century and died in 1952, where thereabouts ended up at Harvard, was born in the Austria-Hungarian Empire. And he wrote a book called Capitalism, socialism, and Democracy in 1942, I guess it was published. And he, he was a critic of Marks, but, and he said that Marx was, you know, that the, the, this thing that Marks and Engels really got wrong about capitalism was that its achievement is not in making more silk stockings for the queens of Europe, but rather for delivering more and more goods at easy prices for the people who produce silk stockings and everything else.

(00:19:02):

And, you know, that is true. I'm, you know, more people have more stuff everywhere. And as you were saying, you know, that gives rise. It does regiment our lives in a certain way because you have to work, but then you have the money from that and across the board you know, it is just cheaper and easier for people to get food, clothing, shelter in terms of time worked everywhere around the globe. There's a wonderful book out called Super Abundance by Gail Pooley and Marion Tupe, that, that documents this in wonderfully intense and, you know, un you know, unmitigated detail. So I highly recommend that. And you know, that is a problem where Marx was right, I think is, you know, that he, he talks about, or he and angles in the beginning of the Communist manifesto, they say, you know, what characterizes bourgeois society or industrial society is, you know, this constant churn of everything that is solid becomes air everything sacred becomes profane, that they're, that cap under a capitalist system, or, and I don't, that term is probably not right under a free enterprise system where individuals have more choices to make and what they want, how what they can buy, what where they can work, et cetera.

(00:20:19):

People are, things are always changing. Shpe in capitalism, socialism and democracy coined the term creative destruction to say that, you know, what characterizes free, you know, market-based societies where there's a, you know, some private property and a lot of choice is this constant, he called them the GAILs of creative destruction, where people want different things over time. And so whole industries and, and, you know, whole fads rise up and down in a, in a given lifetime, so that, you know, around the, you know, in the beginning of the 20th century, you might have, you know, been the maker of buggy whips, and then by 1920 you're completely or virtually out of business because automobiles are, have clearly replaced horse and, you know, horse and carriages. And that, that continues to happen. And it happens in the social sphere as well which I see as a, a gigantic advance for individual freedom and autonomy.

(00:21:15):

We are allowed to seek out how we, you know, what do we desire and how do we create it, and how do we fulfill that? And when we say satiate that desire, we go onto something else, A Marxist point of view, a leftist point of view something coming out of again, you know, I mentioned, I studied literary and cultural studies, and coming out of the Frankfurt school, they looked at the same kind of dynamic that you know, that Schumpeter looked, li looked at. And it's interesting, they we're, you know, they're both central Europeans. All of these pe these, these people were refugees from communism and Marxism. But the Frankfurt school came to a different conclusion and they said, this is, you know, how capitalism enslaves us, or, or it keeps us from actually fomenting real revolution because it keeps giving us new shiny things that we think we wanted, you know, manufacturer's desire and demand.

(00:22:08):

I think that gets it wrong. I think we're we're much more in charge of that. So, you know, but Marx was onto something when he said, you know, that the, the essence, the kind of genius, the motivating force of capitalism is something that, you know, SHPE called creative destruction. And I think we see that now. People are worried you know, that the world always seems to be ending the world. You know, my parents, I'm I was born in 1963. My parents were born in the 1920s. The children of immigrants and the world, their grandparents, the world my grandparents grew up in, which, you know, were rural farms in, in Ireland and Italy. It still exists. There are still literally in both of my, my grand, my grandparents' hometowns, there are the same number of people as there were 500 years ago, a thousand years ago.

(00:23:01):

They, you know, it still exists, but it's so distant from even what my parents grew up in in America, and then what I grew up in late 20th century America. And I find that you know, I find that energizing, I find it liberating. I find it exciting and innovative and forward looking. But I recognize too, a lot of people find that terrifying because it does seem like if nothing lasts forever, you know, how do, how, how do we know how to live? How do we, you know, how do we not go insane with just trying unsated desire or hopping from one thing to another? And you see on the right and the left, you know, historically in, in, in the US as well as the rest of the world, you see different responses to this. But they always, you know, the right and the left insists on controlling people. You have to worship this God. You have to do things this way. You have to pay obeyance to these groups or these traditions to the state or to the business, whatever, you know. And that, you know, is a, it's a, you know, that is, I think, a profound challenge. And it's a particularly intense moment for that kind of dialogue right now.

Ashley Kim (00:24:11):

Well, what do you think is worth worshiping instead? If, if anything,

Nick Gillespie (00:24:14):

I think you know, there's a, there's a couple of things. I, and, you know, worshiping is the wrong term, but I think, and this is where, you know, and, and this marksman as kind of a, a, a strange person within libertarian circles, but again, it reflects both my experience and my education and my kind of analysis, however stupid it might end up seeming. But, you know, this is where I think you meld Nietzche fuco and people like Joseph Shepe, Friedrich Hayek and other Austrian economist who ended up doing a lot of work in, in the United States, but that, you know, what, what has happened in human society is that sometime around 1800, the world changed, where suddenly we moved out of a subsistence world into something that is like a surplus world where as you were saying, you know, we had more goods.

(00:25:09):

We, you know, basically we, we started to cover food, clothing, and shelter to a point now where, you know, 30 or 40 years ago, 90% of the population was, you know, near, near subsistence, you know, on the planet. Now it's fewer than 10% are in ultra poverty as, as it's defined by the un. And you know, what happens when you start to cover the basic, you know, sources of, of need of, you know, basic human needs, food, clothing, shelter, you start to get these things where people, you know, argue for autonomy more and more autonomy, the ability to, to to live the life that they think they want, right? Or that they're experimenting with. And that changes everything. And you go closer to somebody, somebody like Michelle Fuco who you know, is, is is a man of the left, but he was always a critic of kind of Marxist and of central central planning and controlling.

(00:26:06):

And you look at people like Sean Pater and Friedrick Kayak, and they kind of celebrate the ability of more and more people to kind of try to, to, to do what John Stewart Mill called experiments in Living. We've seen this huge shift over the past hundred, you know, hundreds of years. But I think it's accelerated in many ways. In the past 50 or a hundred of, you know, the breakdown of, of gatekeeper institutions of, you know, the church in the United States, the, you know, the number of people who go to church on a, on a weekly basis has declined by about 50% over the past 50 or 60 years. People don't worship corporations the way they used to. I was born into a world where the d the dream job, if you were a man, particularly a white man, and you aspire to middle or upper middle class status, get a job at I B M and they'll take care of you from the time you're in the mail room and you're training to be a manager or a salesman to when you retire.

(00:27:04):

Nobody thinks like that anymore. And it was revealed in the middle of the 20th century that this was a terrible way to live, to be part of a giant cog in a very successful, very powerful, very influential machine. But that was terrible. And that's, you know, the revolt against communism was the same thing. You nobody, nobody wants to be a cog in somebody else's machine. You want to be, you want to build your own machine and deal with people, not where you don't turn them into cogs For you. It's, you know, it's a, it's an i thou world where more pe we all recognize the equality, the essential equality of people, and then you try to persuade people to be part of your life and vice versa and things like that. And that, to me, and to bring it back to Nietzche and Fuco, you know, and capitalism is, you know, the question is how do you live your life as, as a kind of work of art where you are not certain where you're going to end up.

(00:28:02):

You don't have ultimate fixed truth with the capital T, but rather you are groping towards better understanding of who you are, what is important to you, what is important to the people around you? What are the kinds of worlds you want to build and be part of? How do you do that? And so to me, that's what replaces traditions you know, and those can be political, those can be commercial, those can be religious those can be ethnic, et cetera. You know, what, what do you replace systems in which are forced into systems in which you choose? And that, you know, that's hard to do. We, what we have essentially done in conquering global poverty you know, in the past 50 or 60 years, and there's obviously still, you know, quite a ways to go, but we've, we have massified or, you know, mass personalized existential angst. More and more people now have more and more time and resources to wonder about what is the meaning of it all.

Ashley Kim (00:29:02):

Oh, yeah. Well, I was gonna ask you about something similar to Yeah. After the first question, and I think you brought it back very nice, which is that there's a paradox of choice. It seems like we've started to have, where on one hand we have more individualization, more autonomy than ever before. We have tools that our fingertips that no one has had throughout human history. And yeah, it seems like there's this sameness that starts to emerge yeah. Across what people end up enjoying. So there's an article I read from Zero Hedge there, you know, which, which, yeah, I dunno if you're familiar, but I, I, yeah, I imagine I am. Yeah. but, but I've heard it says something that I think is, I've heard similarly, a sentiment that I've heard across a lot of, you know, libertarians, Christians, et cetera, heterodox people. But the idea is that there's a convergence to safeness to some extent, right? Yeah. If you look at the Airbnbs across the world, they all seem to adopt a very similar style. Yeah. the sort of things that are, that are popular on Instagram for like, female features, or very, very similar,

Nick Gillespie (00:29:57):

If you go to, you know, there're yeah, you know, there are like half a dozen or, you know, however you wanna slice it there. You know, let's say there's 20 luxury brands that are now global brands. And so when you go, when you go to an airport or a shopping mall, or, or not even a shopping mall, but the, you know, the, the expensive shopping district in Abu Dhabi or in Las Vegas or in, you know I don't know, you know, Rio de Janeiro or London, they all are starting to look the same, right? You see the same brands, right, the same stores, et cetera. I think there's something to that. And there, you know, I have two responses to it, which is part of it is a result of globalization. And generally globalization has, you know, after a dark chapter where globalization to some degree was forced by colonization and empire.

(00:30:48):

And this is not simply the west colonizing, you know, the east or, you know, however you wanna set up an antimony. But, you know, it's, it's, there's much more flow in all sorts of ways. And certainly you know, the Japanese, you know, colonized Asia, and that was not a Western, you know, et cetera. So, you know, my main point is that we have shifted out of military conquests and into more forms of cultural exchange and cultural change that are closer to voluntary or opt-in, things like that. And that's good. And one of the reasons why things look the same is because maybe a lot of us want the same things. And that one of the great gains, I, I lived fuller part-time in a small town in Ohio for 20, you know, most of the past 20 years or so. And I can tell you, I was there when the New York Times started doing mass delivery to small towns.

(00:31:46):

Like I was there when cable TV fully penetrated the American television market. I was there when Amazon started shipping things everywhere, and it made living in a small town so much better because you still had the small town things, but you could get a reasonable facsimile of living in a much bigger town or in a, in a metropolitan area. And so, you know, part of that globalization, which leads to a sort of sameness, is incredibly liberating for people who don't live in New York, Paris, London, Rome, Tokyo and we shouldn't lose sight of that. It's, it's almost always elites who are bemoaning the fact that when they look at an airplane window, you know, it looks the same to them. You know, it's like, for the people on the ground, their life is better because they have more options and more choices.

(00:32:34):

The other thing though, is to take some of this seriously, but also to look at the places where, you know, change is happening, and individualism and, and experiments in living are growing up all over the place. It's just, you're not gonna find, you know, you're not gonna find cutting edge culture probably in, in the New York City, you know, that we're talking in, because New York is an old ossified city. You never look at the biggest place for the most radical change. You always look at the margins in the same way, you know, that i b m, you know, to go back to that as a metaphor, it was a giant corporation, which meant that it had to be slow moving, you know fundamentally conservative you know risk averse because it had a lot to lose. It's the empire. It's not the rebel.

(00:33:21):

And then you see, you know, whether it's Microsoft or other smaller companies around it eat its lunch because they're smaller and more nimble. And so what we need to be doing, if we're tired of the sameness of certain things, we need to look in the, you know, in the hinterlands, in the places where nobody wants to go, where things radical things are happening. But they are you know, and this is to my mind, what I think people, particularly elites, and, you know, we're all elites here, right? Like, we're the, you know, you're at one of the, you know, most highly regarded institutions, you know, on the planet, right? I'm, I'm, I'm a background of you know, I, I'm highly educated. I've joined the elites. I paid off on the promise of my grandparents, I guess, in coming to America. But we, you know, what I think people often see as sameness is a loss of hegemony, interestingly, of their cultural power.

(00:34:17):

So again, you know, I have a background in literary and cultural studies, and, you know, it's over in a profound way for literary culture. Like they're, they're just the literary culture that existed in mid-century, mid 20th century America, where novelists, you know, like Hemingway or Norman Mail, or Sal Bellow could be culture heroes. It's gone. And if you were invested in that system, you feel pretty bad about that. You don't always know why. You know, TV movie studios corporations, et cetera, they have less and less control over how things happen. Politicians certainly do everywhere in the world. Even somebody like Xi Jinping is struggling to maintain control, you know, and he's a tyrant. He's a, you know, he is an autocrat. He has this more power than any, you know, leader in the world, really. And he is up to his eyeballs trying to keep it together, because we are now living in a world where the more information, more money, more freedom is seeping through the systems. Because the, you know, we've recognized at some point that these systems are much, that there's so much more play in them that it's really hard to control them. So part of the, you know, the, the fears of sameness is it's often that people aren't listening to what I think the world should be like. And that gets mis, that gets projected out on the world as somehow the world is the worst place.

Ashley Kim (00:35:42):

Okay. Well, I'm curious what you describe as loss of hegemony. Do you think you'd better, more actively describe as the rise of hegemony? Because I mean, it seems to be the case that a lot of the things that we described, like the mm-hmm. <Affirmative> predominance of a particular brand, right? Over all laundry detergent, for example, wouldn't be as a result of necessarily these previous, you know, hegemons that end up getting, getting lost to, you know, the new detergents, so to speak, right? But instead that there's just more and more just a single a, a single hegemon, right, that ends up taking over these various things. And I think it's true in the world stage, we'd see, you know, the US versus adversarial nations, we'd see it in, you know, in, in the rise of so-called monopoli monopolies in big tech, even though, right. You know, I don't think it's safe to describe them as that.

Nick Gillespie (00:36:24):

So, yeah, I, I mean, I, I think that that's, those are great questions. And you know, one way to think about it is does the, you know, does the US you know, currently does the US have more or less power than it had? I don't know, you know, 20 years ago, 30 years ago, 50 years ago, a hundred years ago, to change world events. The US can plausibly through, you know, economic sanctions and, you know, dropping bombs and things like that do a lot of damage. But I mean, the last 20 years, and, you know, let's just talk about the 21st century one thing. And you know, what, what we have seen, the, the 21st century has been a demonstration project of the United States, the world's hegemon. You know, we spend more on defense than like the next, you know, 15 countries combined.

(00:37:14):

We cannot occupy and pacify, you know, what Donald Trump would call a couple of shithole countries. We don't have that power. What, what is, and it's, it's awful that we exercised it as if we do you know, and that we occupied Iraq, you know, and Iran, or rather Iraq and Afghanistan, the way that we did to very little effect, particularly in Afghanistan. All we did was, you know, destroy a lot of things and then, you know, welcome the Taliban back in and give them a bunch of weapons we left behind. So I would argue that, you know, this idea that there is a single hegemon in various places, what we're witnessing is really the exact opposite. Or that there are moments where things come up, you know, and if we talk about the the internet or something like that, you know, the internet in the nineties was more dispersed.

(00:38:05):

I think, you know what, what you started to see in the teen, in the aughts, in the, you know, the two thousands was the rise of a couple of powerful players. You know, this includes Google you know, which Vanquish Yahoo, you know, which had been the dominant search engine, but, you know, so be it. But things like YouTube things like Facebook, but Facebook is a good example of in Empire, you know, a virtual empire that is, is losing steam. It's, it, it's had to change its name. It just made a catastrophically stupid bet on VR technology that nobody wants at the exact moment. That AI technology which had been bubbling along is, you know, clearly seems to be a more viable path to the future. And it's not clear who, if anyone can really control that in the same way, but even at its peak, Facebook didn't block out the sun.

(00:38:59):

You know, and Facebook provided, provided and provides a massive function around the globe if we take it outside of a us you know, kind of view. And it has empowered tons of people to coordinate and to talk and to be able to do things, to gain information and to push back you know, in a way that they did not have before. And you know, people will say, well, you know, Facebook facilitated the, the genocide of the Rohingya in Sheri Lanka or whatnot. But the fact is, is like genocides been happening all, all along. What is different actually, is that a lot of the social media technologies, which are, you know, if the companies could have an absolute monopoly and things, they would have them, but they don't. And, you know, and, and they develop things like WhatsApp and you develop you know, stateless currency systems like Bitcoin, which are fascinating and interesting, but in authoritarian regimes, they're an absolute lifeline to getting capital in and out of countries to allowing people to you know, kind of purchase things or to move without having to, you know, be sanctioned by the state.

(00:40:13):

So I, you know, I get the idea, like, we look at, oh my God, you know, like, what was the movie a couple years ago? The documentary, the Social Network, you know, that, you know, like Facebook knows, yeah, I was just listening to a, a, a panel and ex excuse the crudity of this, but the person was like, Facebook has so much information on you. They know when you're gonna take a shit, they are literally up your ass. Right? And it's like the social network came out right as Facebook was essentially peaking in terms of average daily users in North America. They're trying to get their industry regulated so that they could lock in their market position. People are already moving beyond that. And it doesn't mean like they're pure evil, and we have to escape it. It's, it's not like a giant slave plantation.

(00:41:01):

But the fact is, is that, you know kind of hegemons come and go. And the question is, you know, are they more or less powerful? And even again, in places like Communist China you see people fleeing centralized control, or, you know, what the, the Communist Party there is spending so much of its time trying to keep track of people who, you know, they encourage to move to cities. What happens when people move to cities, they become anonymous. They become unmoored from tradition. They become harder to count and harder to find. There's lots of dark spaces where people hang out. And, you know, if it's in Silicon Valley in the 1960s, it's a garage of a ranch house, and they build a new company that blows apart the, you know, the that blows apart the company that the engineers work for during the day. You know? And in China it'll be something else. There's a negative potential to all of this, of course. You know, Germans, you know, getting together in beer halls in the thirties, in the twenties and thirties wasn't, you know, turned out not to be a great thing. They were talking about really bad stuff, but by and large, you know, there's, there's a constant dispersion and decentralization of information, knowledge, and power, I think

Ashley Kim (00:42:15):

Precisely. Well, I think, I think your analysis here is quite apt, and I appreciate it's nuance, you know, cause nowadays we hear either the Doomsday one and the Facebook taking over our lives, but I think it's, it's, it's fair to see the ways in which it has obviously a lot of control and power over these things, but also the ways in which it's inevitably regulated, partially in fact, due its own, you know, stupidity of the people that are running it, which are just regular people. But I'm, I'm curious though, this goes back to the earlier question that you were describing too, when it comes to the rule of the individual and governing these things how do we, how do we ensure then that our preferences aren't being, how do we, how do I put this? How do we ensure that our preferences aren't just being designed for us rather than our preferences are what our designing things in the world? And to what extent do you think journalism helps us get a picture of that? Yeah, that seems to be the, the money question here.

Nick Gillespie (00:43:05):

Okay. Yeah. That's, you know, and it's a great question. And one, you know another thing to think about, and as a backdrop to all of this is kind of generational issues, because, you know, I'm, I, I was born near the very end of the baby boom. You're, I assume, a millennial or a Gen Z even. And you know, a lot has happened in, you know, the, whatever it's been 40 years, you know, since I was an undergrad and not, and one of the most fascinating things to me is that a lot of the rhetoric, whether it was right wing or leftwing or libertarian or progressive, for a good chunk of the 20th century, it was freeing people from constraints. Because everywhere you looked, you know, if people weren't quite in, if man wasn't quite in chains, you know, it, you know, they were struggling against communism and against fascism and against big business or little business or small town values, or, you know, prohibition or what, you know, I mean, there's so many things and so much of the energy and the rhetoric of the boomer generation, and I think this is true of Gen X, it was to getting rid of restraints and constraints on possibility.

(00:44:08):

Like, we just want to be free to figure out what we wanna be. I think for millennials and Gen Z in a lot of ways, and I have a son, I have two sons, one's 29 and one's 21. You know, if anything they have grown up, you have grown up in a world where it's so open-ended it's, it's hard to choose, right? You know, and, and without knowing anything personal about you, it's like, you know, if you've ended up at Columbia, you've had a lot of choices to get to a place like that. And the question isn't like, how do I, how do I free myself from the shackles of everything? It's like, how do I figure out, you know, of, of here's an infinite number of choices of the way that I can make myself meaningful, or I can live a meaningful life.

(00:44:56):

How do I start to decide? That's like a fundamentally diff different question, and it's a much harder one, I think. But it goes to this question that you were asking about how do we know if our preferences or if our desires are kind of authentic or are they manufactured? And I don't know I don't know that there's a really good answer to that. The only way to figure that out is to live and to find out what actually is meaningful to you, because we get everything in these containers and in these rappers that are, you know, part cultural, part biological, part political, you know, part ideological. And I, to go back to, you know, this weird blend of kind of like Fuco and Joseph Schumpeter and Friedrich Hayek or, you know and Nietzche, is that you have to live your life and try to get to, I'm not a fan of authenticity per se, but like, you have to get to a place where you're saying this pleasure or this desire is, is real.

(00:46:00):

It's not, you know, it's not mere fashion, or I'm not doing it in order to please somebody else. And that's a discovery process. And the only way that you discover that is by living and trying different things. And also, this is where the journalism question comes into being. I think by availing yourself of the immense outpouring of journalism, you know, media writing, video music, I mean, the, there is so much material out there to find, you know, what have other people done to figure out what is your personalized vision that is gonna be, I don't know, you know, like somewhere between, you know, and I'm thinking of myself now somewhere between Herman Hess and Lou Reed and Patty Smith and Joan Didion or something like that. You know, like, you have to create your own tradition and make sure that you are living kind of, you know, and I'm being very promiscuous here with the with mixing a lot of different types of ideas in schools.

(00:47:04):

But some, you know, John Paul Sark talked about, you know, living in good faith, like where you are really trying to get to something that is meaningful and real, rather than something that will please the people, you know, that, that have told you this is what you want. Whether it's your parents, you know, whether it's your priest, whether it's your professor you know, and that, and I think the role that journalism or media more broadly or information really plays is, you know, by giving you a lot of alternative scenarios to consider and to be like, wow, that, you know, like, I've read about that. I want to go see that and I wanna see what it's like, or I, I, I'm gonna take, you know, a little bit from that and a little bit from this over here and meld it into my own personalized culture and tradition and meaning. Or I'm gonna find people who are like-minded and create, you know, create a community which may not last our, you know, my whole lifetime, but it's what I wanna be doing now. Having a, a sense of urgency as well as kind of having a sense of urgency too, like that this stuff isn't gonna happen unless you make it happen. But, so you should be an active participant in the mean, you know, in the creation of meaning, identity, culture, society in your own life.

Ashley Kim (00:48:20):

Would it be fair to characterize your political or your philosophy here then as something like data driven existentialism, you know, the idea that you're, the idea that you totally

Nick Gillespie (00:48:29):

Existentialist. Yeah. And, and maybe for sure data driven is, is kind of good. I mean, it's, I don't, I don't think this is gonna show up on spreadsheets or anything like that, but experiential as well as kind of intellectual, I mean, you know, reading is, is, is like the thing that it, you know, it, you can download a lot of stuff, you know, by reading or listening or watching or viewing and keeping your eyes out and traveling and all of that kind of stuff. And I know, you know, on some level, this is all really you know, banal. And it's also something that has been in recognizable form for at least 500 years. I mean, you know, people like John Milton, the English poet you know, when he graduated Cambridge, he went on the grand tour of Europe where you would go to Italy and like, you know, and for English people, you would go to Italy to channel, you know, the, your primitive self, you know, simultaneously Italy, you know, was a site of, you know, the flowering of the Renaissance.

(00:49:21):

So it's like, oh my, it's, you know, the most exalted intellectual and sophisticated place in the world. But it was also kind of like, you know, it was a, a place where you could go to satisfy base urges because southern Italians at least, you know, are, are brute like or whatever. But what I'm getting at is like what we need to be doing now. And I think, you know, I think younger people need to you know, be focused on this. And I think, you know, older people need to be saying, you know what? We need to be doing this kind of self subconsciously, and we need to be having the discussions about what this means to roam around and to find what is true and meaningful and real, and see it as a process rather than a single point oath that then gets enforced on everybody.

(00:50:04):

I think what, what we're seeing in the rise of this kind of mass existential crisis that comes after World War ii, you know, I mean, my parents as children of immigrants, you know, my father was born in Hell's Kitchen in New York to a bunch of Irish people. You know, he was, he worried about food he fought in World War ii, you know, he you know, it was a hard scrabble existence. And after World War ii, it was, you know, it was sold, but like, he had food, he had clothing alter, he, what he didn't have was a meaning in his life. And I think everybody is experiencing that in bigger and bigger terms, which is great. I mean, that's a sign of progress. But we need as a society to kind of recognize that and say, okay, you know what, what we're trying to allow, we need to create an operating system, you know, a social, political, economic, cultural operating system that allows us many people to run their individual programs of life without crashing the system.

(00:51:05):

That's what I think liberal political philosophy actually does in a, in a profound way. But, but then how do you, how do you make people who function well in that kind of free system? And I think when I look at the, and I see a lot of them are trying, looking back to the past as conservatives are wanting to do, so, you know, what we really need to do is ate the 1950s family and that world, everything about it and everything will be fine. You know, we kind of just tell people, here's your job, here's your church, here's, you know, here's your mate and everything's gonna be fine. And you know, of course in the 1950s, people were like terrified, you know? Like, that world didn't exist in the 1950s. It's a, a weird retroactive pro projection onto the fifties. But on the left you see something else where it's you know, identity politics where it's like people cannot mix.

(00:52:01):

And, you know, you can't pick and choose between all of the different parts of you. You have to, you, you get cast as you are black, you are white. You know, Asians sometimes fit in there, but usually not. You know, and, and you know, you're, you're this or that, you're male or female, you're b non-binary or heterosexual or this or that, but like you, it's fixed. It's a weird thing because they get a certain aspect like that. We have a million more, you know, flavors of human being than we had, you know you know, 50 years ago. You know, but they want to say, no, there are only like these five or 10 that are okay, and then we are going to enforce this. So it shuts down the process of kind of continuous creative destruction, not just of the economy, not just of society, of, of the vigil as well.

(00:52:53):

And that's where I think, you know, I guess, you know, media, journalism, conversation, community, that's where that comes into play to be like, no, this is, there, there is no endpoint to this. It doesn't have to be, it doesn't have to be you know, terrifying. It's not like you're on a a treadmill that keeps speeding, you know? And you gotta keep up. You gotta keep up. It doesn't have to be like that at all, but it is a process. And what we wanna do is to make that process more public, more visible, more widely discussed because I think, we'll, I think we'll get along better and more as important will more people will join the conversation. And we'll also have more interesting models from which to kind of think about, you know, what, what does it mean to be alive? What does it mean to be free? What does it mean to live with purpose?

Ashley Kim (00:53:42):

So you're quite optimistic then, does that Doesn't seem very niche, I guess, about the operating system being lost.

Nick Gillespie (00:53:46):

Yeah, no yeah, Nietzche, you know, he was syphilitic. He, of course, he, you know, his brain was literally rotting. Fuco is an interesting character because he you know, died of aids and knew he was dying at a certain point, but he really, and you know, I wouldn't, you know, mistake him for like, you know, an upbeat guy. But towards the end of his life and, and in the seventies, he, he took L s D and he made this turn towards a kind of nian life as a work of art, while also reading Friedrich Hayek. I mean, you know, it's kind of amazing embracing a lot of a kind of libertarian liberal sensibility and became more optimistic that you could live a meaningful life, even, you know, as he's the chief you know, kind of theorist of overwhelming power that is always in everywhere, you know, kind of rigging the game.

(00:54:41):

SHM Pater was a deeply depressive man. I mean, and for good reason. He's, I mean, his biography, there's a great book about him called Profit of Innovation that came out about 15 years ago, literally everywhere he lived, disappeared in his lifetime. Like the village that he was originally from, that region and country was destroyed. You know, it changed. And then, you know, he had to leave Germany or Austria and Germany because of the Nazis, like everywhere he was just disappeared, which kind of makes it interesting that he would talk about creative destruction. But he was deeply depressive, you know, as an individual, I think we can learn from these people. I mean, don't, the one thing we shouldn't take on is their kind of darkness. Because there's actually many reasons to be optimistic. I mean, it's hard. But, you know, the, the, for me, the fundamental question is do more people have more choice in their life?

(00:55:38):

And do they have more possibility of, of living the life that they imagine for themselves free of being told what to do? And it's never perfect. You never are fully clear of all of the contingencies into which you're born, but you can get closer and closer to something that is meaningful. And in that sense, I'm very optimistic. And I also, I feel, you know, I've, I feel like we're going through a period of intense generational change, which is very analogous to what happened when the baby boomers kind of, sort of moving en mass into society, you know, after they graduated college, or in their twenties, which started really in kind of the seventies and eighties, there was, you know, the seventies was a period that was very fraught because people are like, everything is going away. The family is breaking down. Nobody's going to church. You know, the US is about to lose to the Soviet Union. And, but, and, you know, and then it gets okay after that, because it was just, we, we mistook generational shifts for the end of the world. I think something like that is going on now, and I think if we had a more open and honest discussion about some of the stuff I was talking about, we would get through that change a little bit a little bit more calmly.

Ashley Kim (00:56:54):

Wow. Okay. You've heard it here first folks, thank you so much, sir. I wanna be respectful of your time, but it was great hearing about all your FedEx visions of the feature, so to speak. Is there anything else that I'm missing in terms of what your view of what this sort of social fabric will look like eventually? And of course, you know how journalism fits into that, or is that about it? No,

Nick Gillespie (00:57:14):

I mean, I, I mean, I think one of, one of the things to recognize about the media landscape and the, and the journalistic landscape is that there was a, a massive proliferation in, or there has been a massive proliferation in news sources or just in voices. I don't even like real, I like to say news sources, but it's easier than ever for, you know, for people to speak their mind publicly and gain an audience. And, you know, it comes and goes where, you know, sometimes discourse is more centralized, sometimes less centralized and whatnot. But there's so much. And you know, one of the problems with the way we talk about a lot of this stuff, I think, is that no industry has been more disrupted over the past 50 years than, than the newspaper industry in particular. But journalism media more generally you know, the, the number of people who work at daily newspapers, which have been an institution for about a hundred years is way down.

(00:58:12):

You know, and so the, you know, the people who tend to write about this stuff are in an industry that is in a profound way declining or going through such massive wrenching transformations that of course, they project outward and only see misery and dissipation and destruction in the world. And this is where, you know, it's very helpful to be you know, kind of post-modern about this and recognize that the, the, the lens through which, or, you know, that we apprehend reality is, is distorting. You know, or you know, that what I think journalists, you know, to use a phrase that was very common, I know Koran in the, in the eighties, AC Academy journalists constantly are confusing the map for the territory. And what they're mapping is the end of their profession or the world that they thought they were going to inherit.

(00:59:04):

And that sucks. That's hard. It's brutal. It's really difficult to deal with. But we shouldn't mistake that for the reality that is being born all over the place in America, but especially in other parts of the world. And that's, it's a better place. I mean, it's like more are living, you know, period, more people are living longer more people are, you know, groping towards, you know, just defining themselves and living the lives that they wanna live. And that's, you know, that's like, that's not a small thing. That's like, that is the thing. It's interesting. Pretty great.

Ashley Kim (00:59:41):

Yeah, precisely. Well, it's very, it's very reassuring of us to hear of a journalist with such a, would, would you, would you characterize this as boden sensibilities a little bit and innate sort of skepticism towards journalism?

Nick Gillespie (00:59:54):

Yeah, but I, I mean, you know, it's I mean, as if we could talk forever about this kind of stuff, but it's, I mean, a bojo yard in, in very profound ways, anticipated, I think the way we experience reality, what, and the way we mediate it, and all of that kind of stuff. So I would tend to think he's a little bit more pessimistic or kind of conspiracist that things are being foisted on us. I am and I, I think this is partly because of my interest in kind of both in individualism, but also in ki I think understanding better how economics works, that, you know, much less is foisted on us by, you know, these shadowy groups that control everything. And it's more that the market is kind of a process by which we express our desires rather than we have our desires configured for us.

(01:00:46):

But it's always, it's a, it's a back and forth, you know, you, you know, sometimes, you know, nobody knew they'd wanted an iPhone until it was produced, right? But then you use the iPhone to dis discover a world beyond, you know, iPhones or maybe even electronic communications. So yeah, there's so much, I mean, it's, it's just, it's fascinating and interesting. It's a great time to be alive. And my only, you know, regret is that I'm not, you know, 30 years younger because I think the world is gonna, you know, it's been getting more interesting and it's going to continue to, and I hope particularly that younger people who in a profound way are the beneficiaries of the, you know, the wealth and the freedom and the kind of liberation that took place over the past, not just a hundred years, but, you know, 500 years that they, you know, can recognize that and start building on that rather than really feeling defeatist or anxious about the future. I mean, life is always hard, but it's like, you know, this is you, you know, you guys, you've hit the jackpot. You've hit the jackpot because it's better to be alive now than it was, you know, when I was born.

Ashley Kim (01:01:58):

Oh, superbly put. Yeah. I can't help but totally agree. What a gift it is to be you know, young at Columbia, especially given all these cultural, you know, revolutions that are happening right now. Thank you so much for your time and wonderful conversation. I'm really happy to hear all your perspectives on these things.