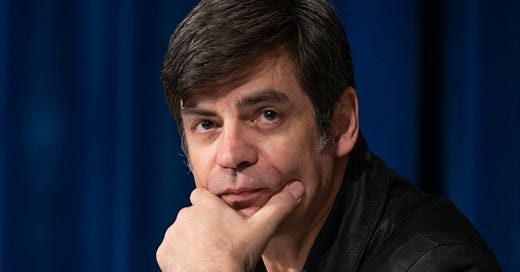

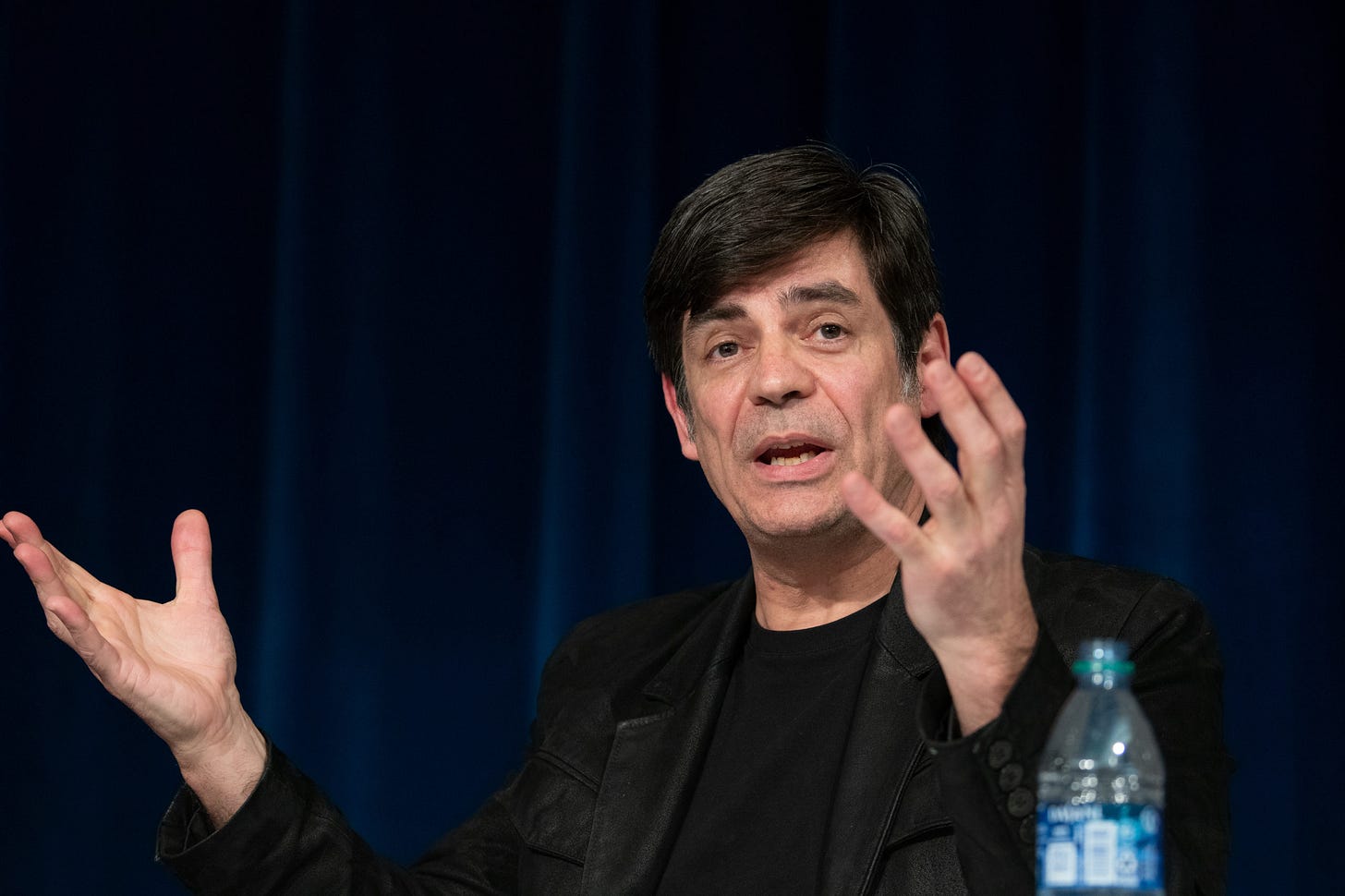

'Nick Gillespie on Academia, Cultural Deregulation, and Libertarianism'

An interview with the Institute for Humane Studies, the organization that in many ways made my career possible.

When I was in grad school in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s (1988-1993, to be exact), I was always getting by on the thinnest of margins economically. My parents were in no position to help me financially. In fact, I started paying full freight on my education beginning with my last year of high school, when it turned out my folks had been stiffing the nuns at Mater Dei the whole academic year. They’d put down a $50 deposit in August 1980 and I was presented with a bill just a few weeks before I was set to graduate in June 1981. I could either pay or not graduate, I was informed, so I coughed up the outstanding balance of $950 from my work savings. (There’s a longer story to tell about my parents’ commitment to Catholic schools they couldn’t really afford and that were in every way worse than the public schools in my hometown of Middletown, New Jersey; I hope to write it someday.)

I’d worked for three-plus years between graduating from Rutgers in spring 1985 and starting a creative writing and English master’s program at Temple in Philadelphia in the fall of 1988. I received a teaching scholarship, which came with a stipend that paid enough to get by on. While at Temple, I met my future wife (and, alas, ex-wife) and we decided to head up to SUNY-Buffalo in the fall of 1990 to finish our doctorates in English. I had an enhanced fellowship at Buffalo (which nowadays calls itself University at Buffalo) that ran out in the spring of 1993, dropping my income from around $11,000 to $8,000 or so (not sure of the exact numbers). Desperate for cash, I applied for a fellowship from a group called the Institute for Humane Studies, which supported grad students interested in the ‘classical liberal’ tradition and advertised in Reason magazine, the one publication I had subscribed to continuously from high school on. The IHS fellowship was worth the princely sum of about $3,000, which helped us out mightily—especially because shortly after I received it, I accepted a job at Reason, which meant we had to move from Buffalo to L.A. in the fall of 1993.

Reason covered $1,000 in moving expenses, less than a third of the cost. My wife was eight months pregnant with our first child and her ob-gyn said she shouldn’t travel by car or truck for such an extended period of time. So we had to fly to the west coast (and fast) and needed to pay for movers rather than doing it ourselves (there’s a longer story to tell about all that, too, which I also someday hope to write down). The IHS grant ended up helping us cover our last expenses in Buffalo and some of our costs to head west, where my wife would finish up her dissertation and I’d work on mine on weekends. (The good news: We both finished up in 1996, and my ex-wife, Katharine Gillespie, is a full professor at Chapman University and one of her generation’s leading scholars on 17th-century British and Colonial American literature.)

A few weeks ago, IHS, which celebrated its 60th anniversary last year, posted this video and article about my experience with the organization and grad school and academia more generally. I’m proud of my association with the group—in the late ‘90s and early Aughts, I had to the privilege of teaching at a bunch of their summer seminars and I’ve also participated in other events since. So I was happy and honored and to talk with them about how their support for me was foundational to my career over the past 29 years. Please take a look/listen and read the article below.

For Nick Gillespie, academia was an absolute joy. It gave him the space to seriously and intensively examine the issues that he most cared about and to learn in ways that would service a career in journalism.

As he was finishing up his Ph.D., Gillespie was hired as an Assistant Editor at Reason, a libertarian magazine that was founded in 1968. His writings brought Reason an unfiltered commentary on culture, infusing its pages with stories celebrating the cultural splashes touching down in areas ranging from television programming to the infinite wonders of cyberspace.

During the final lap in his graduate program, Gillespie received an IHS fellowship — what was then called the Claude Lambe Fellowship — which smoothed his transition by helping to cover moving expenses to Los Angeles, where Reason’s headquarters is located.

“The IHS fellowship enabled me to maintain an uninterrupted flow of studies, as well as get me to Reason’s headquarters in Los Angeles. IHS allowed me to have a career that’s all about the mind and ideas and about the classical liberal tradition.”

– Nick Gillespie

At several IHS summer seminars in the late 1990s and throughout 2000s, Gillespie gave refreshing presentations on the current trends taking place within the cultural arena, reminding students that cultural consumption is now as diverse and manifold as any other good or service on the block. “With the breakdown of certain types of gatekeeper institutions in the late ‘90s,” he says, “the culture had been deregulated.”

The explosion of culture, however, didn’t completely fend off the more defeatist attitudes that continued to creep along as progress was booming. In fact, at these events, Gillespie articulated the many ways in which more cultural choices enhance traditions and values, rather than displacing or shrinking them. What truly became unlocked was not a culture mired in exploitation or depreciating values, but one founded on participation and creativity.

“What was great about these seminars was to see the students respond to a novel way of talking about individual freedom and innovation — the possibility that when you are free to do what you want and create what you want to consume, what is that world going to look like?”

– Nick Gillespie

For example, Gillespie spoke about the emergence of remix culture, where new sounds and videos were being meshed to create completely new products. The ease of access and ability to form your own entertainment, to consume it whenever and however you like, and to share it with countless others was “absolutely electrifying,” he explains.

Throughout his graduate experience, Gillespie cites the advice he was given by mentors and dissertation advisors like the late Mark Shechner, who was an English professor at the University of Buffalo. Gillespie remembers him saying “search for your tribe outside of your department or institution.” This simple note that seeking alternative social circles builds intellectual growth has informed Gillespie for much of his career.

Robert Storey, whom Gillespie met during his graduate studies at Temple University, reminded him that “it’s OK to gravitate sharply towards your passion, but don’t take for granted that it’s the interest of the world.” In other words, share your knowledge with the world and be receptive to what comes back. In the end, intellectual communication is what makes academia a powerful engine of ideas.

Gillespie views graduate school as “boot camp for your brain,” a period in your life when you get to be the author of your own ideas and break into new intellectual spaces. “Graduate school is not really a grind,” he says, “it’s certainty stressful at times, but totally enjoyable.”

Similarly, Gillespie stresses that higher education should not be perceived in strict vocational terms, noting the benefits accrue through methodological and procedural lessons that mark a meaningful education. Graduate school fashions ways of thinking that open new possibilities.

“The real promise of higher education has to be about critical thinking and about evaluating the past and what is good from it. Putting forward ideas, modifying them, and creating a future based on the best that has been said and thought — that is learning.”

– Nick Gillespie

One such methodology that has carried over from Gillespie’s graduate school days and into his work at Reason has been a healthy skepticism, or what Jean-Francois Lyotard labeled as an “incredulity toward metanarratives.” Gillespie believes that the postmodern lens frames much of the world in a way that fits with the classical liberal intuition. He explains that “postmodernism focuses on the limits of knowledge rather than the extent of knowledge.”

For all these reasons, graduate school solidified — and in many cases amplified — Gillespie’s intellectual predisposition toward the libertarian approach. “Graduate school sharpened and deepened my classical liberal intuitions about power and knowledge and treating others equally, without bossing them around,” he says.

On top of this, Gillespie has come to view libertarian as an adjective, a deeply-sowed sentiment that we all have. There is no checklist, no pre-set formula that inducts someone into the halls of classical liberalism — it’s rather a “pre-political sensibility that infuses almost everything we do at life,” he observes.

Thinking back to his IHS experiences, Gillespie notes the many areas of support he received. “IHS provided me with actual material support for a person who did not have it,” he notes. But he also remembers the impact that the books and the people had on him as he was learning more about a tradition that no one else was really acknowledging.

“The IHS community was incredibly smart, modern, cosmopolitical, regional, weird, and wonderful all at the same time. It was like being let into a [hidden] world that exists, but you don’t know it’s there. That sense of belonging to a broader tradition that started before you — and that you can help build and pass onto someone else — was amazing.”

– Nick Gillespie

As he was beginning to identify more with classical liberalism during graduate school, Gillespie was empowered at IHS events to continue learning about this intellectual legacy and exploring new ideas, wherever they happened to lead.

In addition, he was awed by the response that students showed at each IHS program. “To see the reaction of students to a new way of thinking and to a world that maps so incredibly well with the great progress of the past several hundred years gave me a lot of hope,” he says.

Gillespie emphases that there’s a libertarian tradition right in front of us and IHS facilitated his exploration of that tradition. “When I think of IHS,” he reflects, “I think of the comradery and depth. I think of an organization that sincerely mines a tradition that has radically changed the world in a better way.”

The Institute for Humane Studies is celebrating its 60th anniversary in 2021. For more scholar spotlights, video interviews, photo galleries, and in-depth conversations on classical liberal ideas, visit TheIHS.org/60.

This is a great intro to Nick's worldview.

PS: I think you have your high school graduation year wrong.