Occupy Wall Street & Fake Campus Progressivism

Musa al-Gharbi's We Have Never Been Woke demystifies how elites maintain their position--and why more working-class Black and Latino voters support Trump.

Scroll down to start watching or listening now.

This week’s Reason Interview podcast is up—and it’s a great (and timely!) one.

Musa al-Gharbi is a sociologist at Stony Brook University and the author of the new book We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite. Al-Gharbi argues that academics, journalists, and other elite professionals that he calls "symbolic capitalists" are disconnected from the marginalized and disadvantaged communities they claim to speak for or represent—and that, by using the rhetoric of class solidarity drawn from the Occupy movement (which pitted the "99 percent versus the 1 percent"), progressive symbolic capitalists actually exploit those communities to maintain a relatively lush lifestyle.

Born and raised in a mixed-race military family in Arizona, al-Gharbi spoke with me about how wokeness transformed the college experience, his conversion from Catholicism to atheism to Islam, why black and Latino voters appear to be embracing former President Donald Trump in record numbers, and his highly public cancellation in 2014 after he was attacked by Fox News for criticizing U.S. foreign policy.

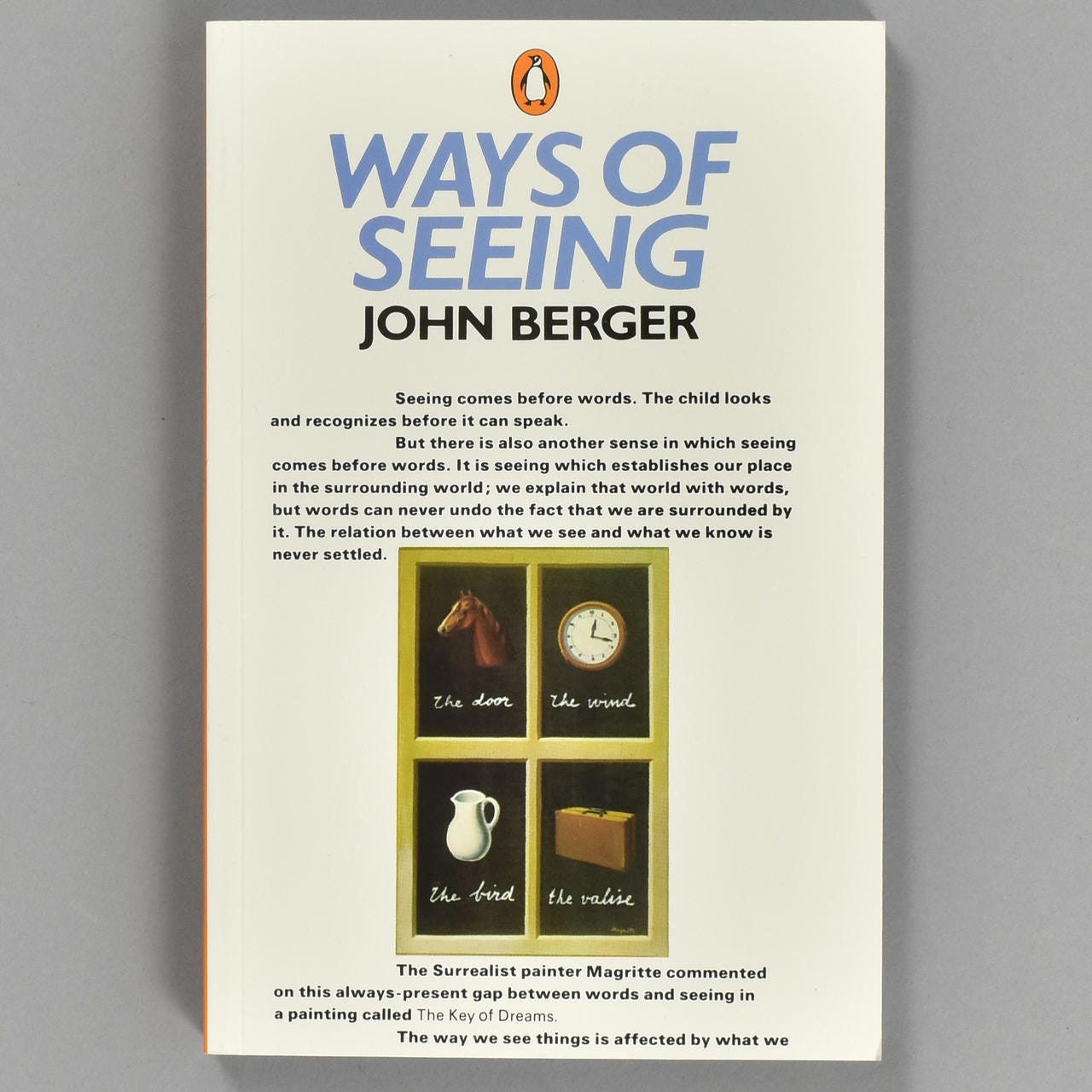

He uses the concept of mystification in his book and our conversation. I first encountered mystification in John Berger’s incredible Ways of Seeing (1972), a Marxist analysis of art and interpretation that has stayed with me since reading it in grad school in the late 1980s. From a hardcore Marxist point of view, mystification is the sometimes-intentional, sometimes-unintentional process by which we come to assume that things are the way they are because that’s how they should be—due to natural laws maybe, or God, or meritocracy, or because that’s how they have always been. Each economic system or base creates a cultural and political superstructure that rationalizes and supports it, making it seem not just inevitable but just. Feudalism conjured a strictly hierarchical Catholic Church and the Great Chain of Being as a way of keeping people in line, while capitalism benefited from (or caused?) the Reformation and a series of beliefs in things like individualism and competition to make people keep with the program. At various times, the ruling class has to crack skulls, but the whole point of mystification is to keep the need for actual violence and open repression to a minimum.

Elites benefit from mystification because it maintains a status quo in which they are privileged. From a hardcore Marxist perspective, for instance, we have naturalized or normalized an economic system in which some people are very rich and some are very poor—not because things have to be this way, but because we have been taught to believe this is they only way they can be. The old South mystified race relations by invoking religious, scientific, and/or moral explanations to keep things the way they are, etc. In terms of gender, I come back again and again to the fact that girls didn’t do pole vaulting when I was in high school—because it was a biological truth that they didn’t have the upper-body strength to do so. No system is perfectly sealed of course and things change over time for all sorts of reasons, including natural disasters, technological innovation, and political unrest.

One of the reasons Marxists emphasize history (the literary critic Fredric Jameson’s famous cry is, “Always historicize!”—that is, put things in a proper and usually subversive context) is because it gives us access to different perspectives and to question whether the current moment is in fact the only or best ways things should be. In the first part of Berger’s Ways of Seeing, he examines the work of the 17th-century Dutch painter Franz Hals in the context of mystification and argues that we have been conditioned to see such paintings as legitimating an economic system that had left Hals destitute in his old age. He zeroes in on Hals’ last two major paintings, of the governors and governesses of the very alms house in which the artist was living and on whose charity his life depended. Berger points out that the leading Hals critic goes through a lot of work to ‘prove’ that ‘there is no evidence…that Hals painted them in a spirit of bitterness.’ Rather, the critic works overtime, using very vague, high-minded, and imprecise language to say Hals instead created a ‘marvellously made object’ that reveals an unchanging human condition.’ But if you actually look at the people in the paintings, Berger says, you can kind of guess what Hals really thought of them—these are in no way flattering portraits. ‘Mystification is the process of explaining away what might otherwise be evident,” says Berger.

I don’t agree with Berger about capitalism, but Ways of Seeing forever changed my relationship to culture, especially high culture (somewhere in that text, he points out that libraries and museums, which are almost always sold to taxpayers as ways of edifying the lower classes, are patronized overwhelmingly by the wealthy and educated few). If you believe in public choice economics, you are already hip to how mystification is used by the public sector to enlarge its sphere of influence and power. Teachers almost never invoke self-interest. Instead, they say they are doing it all for the kids. Doctors aren’t greedy—they’re noble healers who don’t want to talk about money because human life is priceless. The socialist historian Gabriel Kolko demystified the Progressive narrative about railroad regulation and antitrust actions in the early 20th century by demonstrating that it was actually the big firms who called for and benefited from the regulation that supposedly brought them to heel.

What does this have to do with Musa al-Gharbi, who isn’t a Marxist? His book attempts to demystify wokeness and goes a long way to doing so. I was particularly impressed by his reading of the Occupy movement, whose rise marks the beginning of the current ‘Great Awokening’ in which we find ourselves. It was an incredibly smart and mystificatory move, says al-Gharbi, to create a class analysis that pits the 1 percent against the 99 percent. Why? Because it puts the students at places such as Columbia University, where al-Gharbi got his Ph.D., on the same side of the divide as truly poor people even if they have nothing in common. According to the New York Times, just 21 percent of Columbia’s students come from bottom 60 percent of U.S. households, but who’s keeping score, right? Colleges now are big on tracking the number of first-generation college students because that suggests upward mobility, which is a good and honorable thing in a merit-based society. Al-Gharbi writes that the University of Pennsylvania considers you a first-generation college student if your parents merely went to a state school! Indeed, in our conversation, he notes that your parents could have Ph.D.s from UCLA but you would still be counted as first-gen at Penn. That is very generous of Penn!

This is mystification at work. It’s good to recognize it and call it out. And to always be thinking about how we frame our analysis of whatever it is we are talking about, whether it’s Dutch painters, the children of plutocrats cosplaying at radicalism or poverty, or narratives about how some professions act only out of altruism. We needn’t become cynical about things, or anticapitalist. I’m with Schumpeter on that latter point. He saw that what capitalism did was to bring more stuff in reach of the lower classes even as it helped erode inherited wealth and status (in this, he was like Marx and Engels, who had some good things to say about bourgeois society in The Communist Manifesto).

I think that al-Gharbi has too dark a take on the current service economy, but his insights and analysis are really interesting and important. Let me know what you think.

Here’s a summary of what we talk about:

0:00— Introduction

1:09— New book: We Have Never Been Woke

4:04— Can 'wokeness' be defined?

8:35— The history of 'Great Awokenings'

9:30— Occupy Wall Street was an elite movement

11:02— 'Symbolic Capitalists' pretend not to be elites

15:57— Political splits among 'Symbolic Capitalists'

19:50— The primary function of elite schooling is to grant elite status

23:42— Cultural contradictions of 'symbolic professions'

25:20— Elite overproduction drives status anxiety

27:30— Elite overproduction and popular immiseration equal 'Great Awokening'

31:04— How Occupy Wall Street shifted to identity politics

34:46— Victims like George Floyd only become important to elites after symbolic martyrdom

39:22— Musa al-Gharbi's background

45:00— Being canceled by Fox News

49:00— Engaging with conservatives

53:18— Attending Columbia University

55:11— Working with Heterodox Academy

57:40— The latest 'awokening' is tapering off

1:00:29— Realignments among Black & Latino voters

1:06:42— Better living standards shift politics into 'post-materialist' frames

1:09:08— On not voting in the 2024 elections

Today's sponsor:

The Reason Speakeasy. The Reason Speakeasy is a monthly, unscripted conversation in New York City with outspoken defenders of free thinking and heterodoxy that doubles as a taping of The Reason Interview With Nick Gillespie. The next one takes place on November 18 and features Mercatus Center visiting fellow and former CIA analyst Martin Gurri, whose decade-old The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium remains one of the most important guides to the 21st century. Go to reason.com/events for information and tickets.

If you like my work here, read and support Reason!

Fascinating listen.

While I will agree with Al-Gharbi 100% regarding "symbolic capitalists" and the "woke" cultural movements as being those of the elite that definitely employ mystification to obscure and conceal while manipulating understanding using complex and vague language to keep people from fully grasping the underlying truth of what is happening and what they are doing (exploiting other people's pain for financial gain more often than not, almost always in my opinion). I also find it ironic that he is a believer in Islam. It is understandable given his described path to that point as he obviously needs to believe in a narrative or his coping with life is difficult. Islam definitely does not think of itself as a "new" faith but the absolute and final revelation. Anyone who can agree with that from the text, can recognize the threat of violence undergirding the demand for respect of that fact by Muslims. Otherwise they tend to employ violence rather quickly throughout the world despite the cafeteria style buffet picking and choosing that certain Muslims employ to justify violence or irreconcilable issues such as the Prophet Mohammed was betrothed to his favorite wife Aisha when she was 6 and took her as a wife when she was 9. I am sure there is a mystification explanation.