Talking about Punk as a "Cultural Antibiotic" for the Body Politic!

A great conversation about why the Ramones, Sex Pistols, Clash, and others mattered so much, but for so brief a time. And why we need a new blast of that old punk magic.

Apologies for the long, long, long absence—especially since this list is supposed to be a place where I drop media appearances and other things that don’t show up normally at Reason’s website! The Compleat Nick Gillespie? As if!

I pledge to do better on that score and my first step toward amends is to share this recent podcast I did with journalist (and friend) Eli Lake (follow him on Twitter). And I highly recommend you start listening to the episode right now as you read!

Here it is on Apple podcasts:

And here it is on Spotify:

Eli mostly writes about national security issues at places like Commentary (archive), Bloomberg (archive), and The Daily Beast (archive). Sometimes we agree (read his great 2010 Reason piece, “The 9/14 Presidency”) and sometimes we don’t, but I always learn a huge amount from everything of his I’ve even glanced at.

He is a true music nut, though by dint of him being a decade or so younger, growing up in Philly rather than the NYC area, and a million other factors, our tastes are quite different. His deep, deep knowledge of hip hop and certain forms of pop dazzle me, as does his ability to keep up with something that I mostly gave up on in the early ‘90s. Parenthood was calling me in 1993, when my older son was born, and so was my job (I started at Reason just a month before becoming a dad) and there was so much more stuff I was doing without the spare time or change to stay abreast of what was new and exciting in music. It was a big shift, as I had always really been into music, second only to literature to me as an art form.

As you may know, back in the day, I was a journalist working for second-, third-, and fourth-tier mags such as Metallix: It’ll Rock You to Shreds! and the US edition of Smash Hits) and I still proudly bill myself as almost certainly the only journalist who has interviewed rock stars such as Ozzy Osbourne and Slash and Nobel laureates such as Milton Friedman and Vernon Smith. But my tastes have always been excruciatingly narrow, rarely straying from worshipping at the feet of the Great God Rock ‘n’ Roll and its close cousins (folk-rock, psychedelic, punk). Born in 1963, I mostly grew up in the ‘70s and ‘80s, and my musical tastes were for a long time bounded by what my older brother John (four years older than me) brought home from record stores and, later, college. He was into Led Zeppelin, The Who, The Beatles, Yes, Genesis, and especially loved Elton John during Captain Fantastic’s tremendous run in the Me Decade. Sometime toward the end of the ‘70s, my late hippie cousin John Guida gave me a ton of records he’d collected over the years, including stuff by The Byrds and other ‘60s folk rockers and psychedelic bands that blew my mind and sent me scurrying to my hometown’s library for similar stuff.

I was certainly a fan of all that and a lot more of what I would hear on the AM radio in my parents’ car—I love to celebrate the end of mainstream culture but there’s no doubt that the Top 40 during the ‘70s was something wonderful to behold. Consider this list of Billboard’s top-selling singles from 1973, when your humble narrator was just 10 years old: Tony Orlando and Dawn’s “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree” was the biggest hit in a year that also coughed up tunes as wonderful and weird as Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly with His Song’ (#3), Paul McCartney and Wings’ “My Love” (#5), Billy Paul’s “Me and Mrs. Jones” (#15), Edgar Winter’s “Frankenstein” (#16), Cher’s “Half-Breed” (#20), and Grand Funk Railroad’s “We’re an American Band” (#23). Crammed into a family car with two or three generations, you never knew what was going to come up next and, as often as not, offend the mom or dad driving with a three-minute serving of simulated sex and/or a paean to jailbait.

Of course, no punk music ever made it onto AM radio—it barely made it onto FM radio, if I recall correctly. But I can remember my brother and I reading about The Sex Pistols going on England’s Bill Grundy program in 1976—an appearance that is still hilarious to watch (though I wouldn’t actually see it probably for 15 years or more, until it became available on the internet). It was written up in The New York Post or Daily News and I remember us laughing at the idea that fussy old Brits were so incensed by “the filth and the fury” they witnessed that they kicked in their TV sets in disgust.

Closer to home, New York City was becoming home to “punks” who dressed, well, like we all dress today, in jeans and t-shirts and thrift-store clothes, and acted pissed off a lot or just goofy. The girls often dressed like boys, who sometimes dressed like girls or would occasionally sport mohawks or other complicated hairstyles. They were mad not just at the folks we would later call the Greatest Generation but at older Boomers too, something with which I identified intensely. By the time I started high school in 1977, I was already being lectured by teachers who claimed that they’d been at Woodstock that kids my age were nihilistic, shiftless, unidealistic, and indifferent (charges to which we would of course merely shrug, enraging them all the more). Weirdly, one of the great prog-rock bands that inflamed Johnny Rotten and other punks with their bloated stadium shows and long, endless solos, Pink Floyd, provided a punkish, anti-authority soundtrack to my high school years by releasing The Wall album in 1979. Musically, it’s as different as can be from The Ramones, but the message was the same: Hey teachers, leave them kids alone!

I listened to the old FM radio station WNEW back when it was a rock station, drawn especially to Scott Muni’s “Things from England” show, on which he would showcase upcoming acts such as Elvis Costello, Graham Parker, the Clash, the Jam, and the Police. I loved the rawness and anger of much of the stuff—but also that it could be funny too. What’s not to love about bands that called themselves names like The Dead Kennedys and released songs like “California Uber Alles” (1979) that mocked the “zen fascism” of Gov. Moonbeam (Jerry Brown), and “Holidays in Cambodia” (1980), a piss take on commie-symp sandalistas? Blondie’s Debbie Harry somehow managed both to embody and critique conventional Hollywood sexuality in a way that titillated and scared me, and Patti Smith and Chrissie Hynde introduced what seemed to be a totally new female identity to rock music, somehow light years beyond whatever The Runaways, themselves pathbreaking, had been vamping only a couple of years before.

For some reason, the cloud of signifiers that defined punk for me—loud, comic, anxious, angry, fearful, funny, ugly, cool, don’t give a fuck, non-conformist, etc—spoke to me in ways they didn’t to my siblings or most of my friends, who tipped more to the happy, mainstream nostalgia of, say, the Travolta-Newton John version of Grease while I grokked its shadow version, the Ramones-inflected Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, an equally implausible musical set in a world where high school is exclusively populated by actors who seem to be in their 40s (Besides about $366 million in box office, the real difference between Grease and Rock ‘n’ Roll High School is that Vince Lombardi High literally gets blown up at the end of the latter film). There’s no accounting for taste, but when Jack Klugman, in the wonderfully awful “punk rock episode” of Quincy asks, “Why would anyone want to listen to music that makes you hate,” well the question just kind of answered itself for me for a while. (Yes, Eli and I talk about that particular show, which is so, so great.)

My relationship to punk—and my appreciation for the broad movement it represents—has evolved and changed over time. As I discuss with Eli, I’ve come to see punk less and less as anything approaching a coherent aesthetic, style, or even attitude. I view it more and more as a specific moment in time or burst of energy in the mid-1970s borne out of desperation, exhaustion, boredom, and a deep recognition that “the system” (economic, cultural, political, whatever) not only didn’t care about you but was incompetent too. That was true of the adults in charge of politics (Gerry Ford, Jimmy Carter) but also culture (Disney produced awful movie after awful movie). Everything seemed played out, good for a laugh maybe. Even the older Boomers and hippies had revealed themselves to be terrible and devoid of wisdom or staying power. By the late 1970s, the only thing people feared more than getting hit by a chunk of Skylab falling from the sky was the release of new solo album by one of the Beatles.

That broad sense of despair also created a sense of opportunity, too, that infused punk. “Anger is an energy,” Sex Pistols’ frontman Johnny Rotten would come to sing in a song for his follow-up band PiL (it’s also the title of one of his memoirs). When god is dead, all things are possible, whether the god is Eric Clapton or Richard Nixon or Jim Jones. It only takes a bit of initiative and the right mix of literal and figurative uppers and downers. But as The Sex Pistols could tell you, punk energy, anger, and even humor is also unsustainable. It burns through everything.

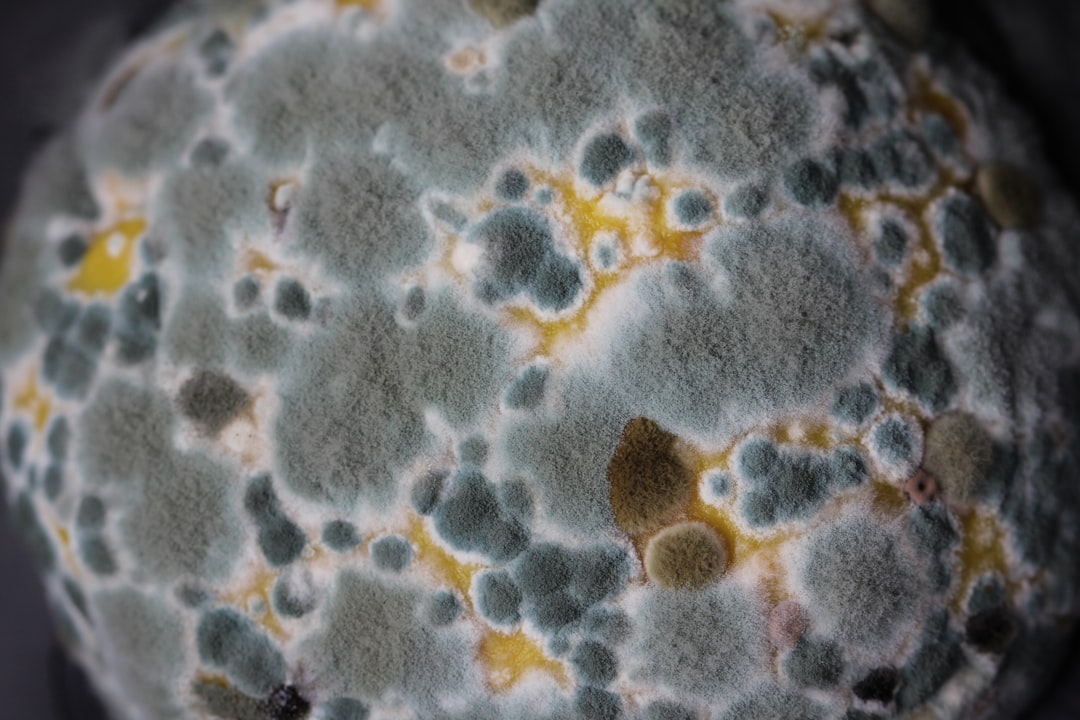

These days, I like to think that punk acted as a cultural antibiotic that cleared out a lingering gut infection in the body politic of the United States and England. One popular reading of punk is that it was a response to the rise of Thatcher and Reagan, which is just beyond stupid. The defining moment for punk was over before they came to power; indeed, they are best understood as the products of the same forces that gave rise to punk (there’s a good story in the podcast I tell when Johnny Rotten interviewed me on this point on a short-lived web-radio show he had in the early 2000s). As I wrote at Reason when Thatcher died in 2013, “Shrinking the state and shrinking the excesses of Emerson, Lake & Palmer were not, I argued, really all that different (I humbly submit that ELP's Brain Salad Surgery is the prog-rock equivalent of an 83 percent top marginal income tax rate).”

The punk movement and moment, I think, remain important to study and appreciate, especially in today’s age of lassitude and torpor that calls to mind aspects of the 1970s. God, we’re all so fucking tired of the status quo but don’t have the courage or desperation to jump feet first into the 21st century! We needn’t define punk too tightly or academically to understand that it helped burn off a bunch of cultural and political garbage that had built up over the decades of the post-war era. Punk cleared the decks so we could move on to something new and different, right at the moment when we were choking on a bunch of awful cultural and political impulses that were played out but still clogging up everything.

That sounds a lot like today to me, where we have two major political parties that are as dead as Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen and where we are constantly fighting over the past rather than just getting on with the future already. How many more reboots of old shows do we need, whether we’re talking Lord of the Rings or the 2020 election? At the same time, punk simply isn’t capable of creating a stable culture. It is at its core an iconoclastic energy that is better at tearing down and sweeping away than constructing a new world (in this, it calls to mind Martin Gurri’s thesis about new forms of online organzing in The Revolt of the Public). The Ramones are better when they are beating on the brat than when they are searching for something to believe in.

A figure worth thinking about in this context is Iggy Pop, the great proto punk who like some ancient Greek or Roman hero who gave all on stage a million times over and absolutely descended into a personal and professional hell before reemerging from the underworld like some weird, wonderful version of Tiresias, the blind prophet who has seen it all and done it all and has the wisdom that comes with age and experience. But Iggy is so much better than Tiresias: He’s made raw beauty out of the wastelands of the post-industrial Midwest and of New York at its most down and out; he continues to grow and develop as an artist and to inspire artists who are young enough to be his children but still can’t keep up with him. He reminds us all that however powerful, necessary—and fun—punk can be, it only works as a prelude to the next thing.

Thanks for reading—and for listening to the podcast with Eli Lake, which I’ll embed one last time right here:

I think it's a mistake to view punk rock as a movement. There's nothing tying it all together but cynicism and music and individuality. Not even fashion. Ironically, this means it is never out of fashion.

We've had "punks" for centuries. First one I found was Diogenes of Sinope.

I loved your conversation with Eli, and listening to you and Matt Welch talk weekly confirms my belief that late Boomers (the age of my cool aunts and uncles) and early Gen-Xers (the age of me, their annoying nephew) have much in common when it comes to pop-culture tastes and related sensibilities.

I struggle to connect with much music made after 1993 or '94, which perhaps not coincidentally was when I was beginning to tire of grad school and eager to get on with a married, mortgaged life. Like you, Nick, I see the cultural-political conditions of punk's golden age to be much like today's and anxiously await a new wave of creative young musicians to emerge, disgusted by MAGA, COVID policies, InstaTok, crappy Disney content, and the rest. I am sure there are other examples out there, but the only one so far to catch my attention is Yard Act out of Leeds. I would love to hear other suggested acts to check out.