‘Simultaneously Very Funny and Deeply Worrying’

What the World Is Really Like: Nick Gillespie Talks Humanities, Free Speech, What Motivates His Journalism, More

Nick Gillespie began reading the libertarian monthly Reason as a teen. Coincidentally, so did I. My dad was a subscriber from the early days of the publication. I thumbed through the stacks in his office while eagerly awaiting the next issue.

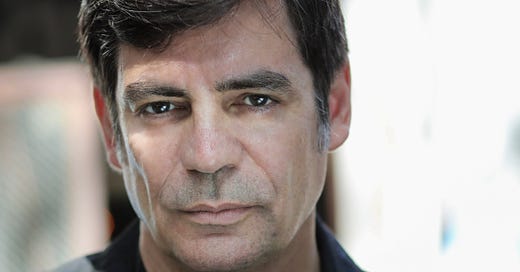

That’s where I first encountered Gillespie and his work. He didn’t just read Reason; he went to write there and eventually became editor-in-chief for a stint. Now editor-at-large, he’s since taken on several different projects for the magazine, including launching their video initiative, hosting the Reason Interview podcast, and more.

Gillespie is the coauthor of The Declaration of Independents and the editor of Choice: The Best of Reason. He’s written for such outlets as The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, Time, The Daily Beast, and many others.

As a journalist, Gillespie always brings a deep cultural sensibility to his work. I wanted to hear more about that. So I asked him. Be warned: He gets spicy.

Miller: We often hear about the longest-dying discipline in American higher education: the humanities. But while as an opinion journalist you’re known for political, economic, and social commentary, you have a PhD in English literature. What role do the humanities play in how you understand politics and culture?

Gillespie: The short answer is pretty much everything.

In The Counter-Revolution of Science, Friedrich Hayek wrote that literature, philosophy, history, and the arts open up “the great storehouse of social wisdom, the only form indeed in which an understanding of the social processes achieved by the greatest minds is transmitted.” Contra the Harold Blooms of the world, I don’t spend a lot of time arguing about whether something is great or deserving of canonical status (as opposed to whether a text or idea is important to a particular group or reveals some significant dynamic or belief about the world). But it’s the humanities that give perspective to all of the other things that have helped so much with material progress.

Understanding the past is absolutely essential to having a full, rich appreciation of our limits and our aspirations. And that comes through a study of what has come before us—in terms of history, philosophy, and art. How can any of us situate ourselves in this world of nearly infinite choice if we don’t create a genealogy that helps explain from whom we’ve descended (figuratively more than literally)? How do we know what direction to head towards (or away from) if we don’t know the past?

Too many people today—old every bit as much as young—exist in a vacuum, either experiencing everything in lonely isolation or hubristic exceptionalism: The world didn’t exist before I was born, I alone think/believe the way I do, that sort of thing. The humanities don’t provide cocktail-party conversation starters or arm us with the “right” opinions so we seem educated or “finished”; they allow us to define ourselves and improve ourselves. They’re the stars by which we set our course.

It’s deeply depressing to me to see the humanities—at least at the university level—continue to decline, especially when it comes to literary and cultural studies. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, there were about 64,000 literature majors in the 1970–71 school year. In 2020–21, that number had declined to 36,000, even though the number of bachelor’s degrees granted annually had increased by 2.5 times to 2.1 million during that time span.

Part of that decline is doubtless due to broad trends far outside the power of English profs. I’ve long been critical of the view that college is a form of expensive vocational school, which has really come to dominate discourse on both the right and the left. It drives me nuts to hear parents, who might be second-, third-, or even fourth-generation college grads telling their kids that humanities are bullshit degrees and the reason you go to college is to get a job.

You’re going to learn your job when you get out and get hired somewhere. What the humanities can do is orient you toward the bigger picture and begin to give you a sense of how our predecessors thought about the existential questions we all need to confront. This is partly because college is perceived as being so expensive that you can’t afford to dick around with things like literary and cultural studies. But it’s really more about status, I think, and a failure of nerve by parents and students alike.

What the humanities can do is orient you toward the bigger picture and begin to give you a sense of how our predecessors thought about the existential questions we all need to confront.

—Nick Gillespie

While noting those larger forces, I don’t want to minimize the role that literature professors and those in related fields play in driving down interest in, and respect for, the humanities. I was in grad school from the late 1980s through the mid-1990s, the period when what was then known as political correctness really came to the fore.

Between the start and finish of my grad education there was a palpable shift from a 1960s attitude of mostly open debate and discussion about everything to a much more apocalyptic one, especially after George H.W. Bush easily beat Mike Dukakis and academics started to feel like they were trapped in a country they didn’t understand or want to understand. It was bad enough that Ronald Reagan—an actor who got second billing to a chimp!—had become governor of California, but then he became not just president but the most significant president since FDR! And then, his empty-suit VP got elected! Academics felt like they had lost their country.

Having said that, the professors I had who got their doctorates in the late 1960s or before were of course all liberal or progressive. But they were mostly into the idea of arguing about stuff and following ideas and new analyses to novel conclusions. The ones who’d come of age a decade later were more like ministers who were teaching young preachers the one correct interpretation of the Bible so that they could go out and enforce a single reading of every aspect of American culture.

The university wasn’t an experimental space, a place to work out ideas. It was a training ground to turn out a sales force who would fan out across the country pushing a particular product—a sort of elitist, contemptuous view of everyday life pulled from parts of Marx and Freud, that mostly held people were completely hoodwinked and shaped by forces they couldn’t quite understand. Everything was “determined” by economics, psychology, capitalism, etc., to such a degree that no one, except the wise professor of course, could see through the manipulation.

They were working off a script that in its high-end version was articulated by Adorno and Horkheimer in Dialectic of Enlightenment and in its popular version by Vance Packard in The Hidden Persuaders. The supposed cultural contradictions of capitalism hadn’t gotten bad enough to wreck the system, but just you wait. This wasn’t about poststructural or postmodern theory, by the way. It’s impossible to actually read Foucault, say, today, and not see his libertarian and individualistic sympathies. (He even exhorted Hayek and Mises in some of his last lectures in Paris, and the recent book The Last Man Takes LSD explores this wonderfully.)

We didn’t know it at the time, but these were the waning days of the Soviet Union and the whole idea of command-and-control economics and culture was about to give way to the more decentralized, gatekeeper-less economy of the globalized 1990s and the internet revolution. But lit profs were mostly sour and turned against new forms of cultural production that really empowered alternative and individual expression.

In one of the greatest intellectual blunders of all time, too many humanities profs became convinced that things were bad and getting worse right as cultural production and consumption was being radically deregulated due to technological innovation. No wonder students turned off and dropped out. They were sinners in the hands of angry professors.

Luckily, of course, the university has never defined our culture any more than it has our business practices. But I wish the humanities, or at least literary studies, had a different, more positive valence.

No wonder students turned off and dropped out. They were sinners in the hands of angry professors.

—Nick Gillespie

Something I’ve always appreciated about the Reason Roundtable podcast: at the end of each episode of current events is the what-we’ve-all-been-consuming-in-the-cultural-sphere feature. Someone could easily see that as superfluous, but you all contribute every week. How did that feature come about?

I’m not sure. It’s definitely not peripheral to the show, any more than cultural consumption is peripheral to what it means to be libertarian. I’d love to do a full episode where all we do is discuss what we’ve been reading, watching, etc.

We’ve been producing video and audio content since 2007, including a very odd and wonderful talk show that was explicitly modeled on the way Kramer revived the Merv Griffin Show on Seinfeld; we also published audio versions of all our video content from the beginning. We started doing actual podcasts in the fall of 2016, and the Roundtable came together in its current format (host, plus three staff regulars and occasional guests) in 2017. We split Reason’s podcast feeds into separate streams a couple of years ago. (Prior that, all our audio went out on a single feed.)

Katherine Mangu-Ward, Peter Suderman, Matt Welch, and I all consume much more than we could ever really write about, and this gives us a way of talking about the books, movies, music, and other forms of creative expression that we wouldn’t get to otherwise.

Before I went to grad school, I worked as an editor at various music, movie, and teen magazines, so I’ve been in love with popular culture my entire life, and I’ve never really found it that useful to draw distinctions between high and low, classic and ephemeral, etc. (I went to the State University of New York at Buffalo for my doctorate specifically to work with Leslie Fiedler, who really pioneered this attitude in the postwar academy.) I think the last five to ten minutes of the Roundtable are often the most meaningful, especially if we disagree about a particular work.

What are your top-five novels for explaining American culture? What drives your selection?

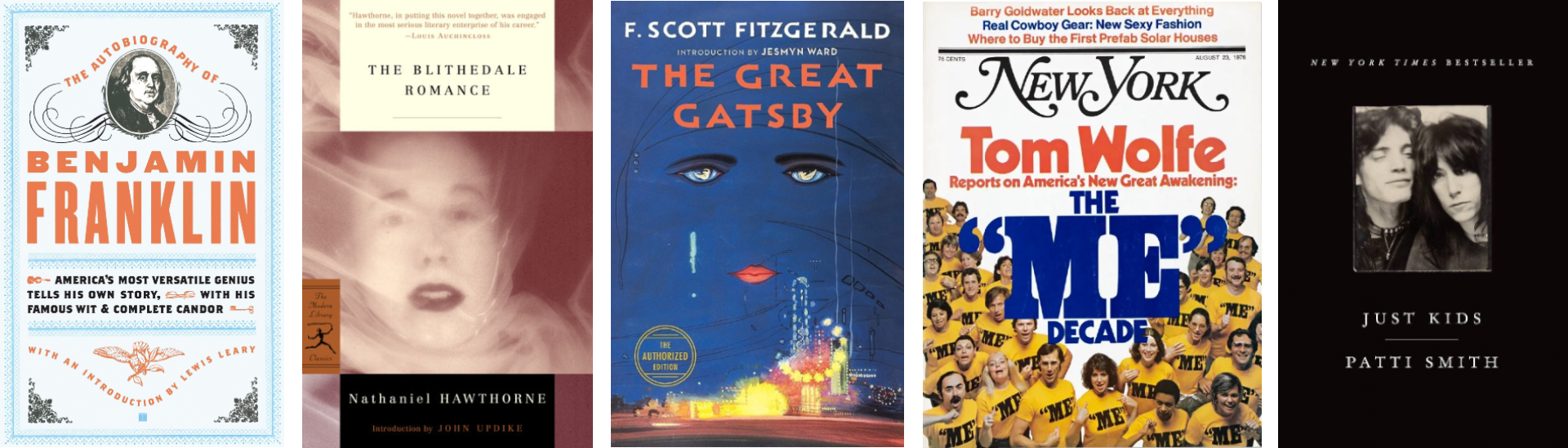

I’m going to get squirrelly and throw in some literary nonfiction and autobiography (which is such a prominent fixture in American letters, I think). But here are some works that I think really help explain the America we live in. Each in its own way is about the intentional creation of the self and the limits of that:

The Autobiography of Ben Franklin. If I believed in nationalist essences, I’d argue this is the book all American identity begins with. The runaway nobody who becomes the most famous and consequential person of his era. It’s arguably the first great American self-help book, in which he explains to his son (and all readers) how he made his way in the world, giving us mere mortals a basic framework to riff off and turn to our own ends. He didn’t have to do that.

D.H. Lawrence called Franklin the “first dummy American,” and that’s ultimately a compliment: He’s a dummy like a mannequin on which we can hang our own clothes. His description of how he “emerged from the poverty and obscurity in which I was born and bred, to a state of affluence and some degree of reputation in the world” echoes throughout subsequent American writing.

The Blithedale Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne. A tale set at an unbelievably annoying utopian community not unlike Brook Farm, where Hawthorne toiled briefly and unhappily. This novel, which is relatively underappreciated, is a tragedy of idealism and epistemological hubris in which the three main characters, including the very droll and very unreliable narrator, jockey for power over a fourth character.

Spoiler alert: It ends poorly because the characters can’t grant agency or equal standing to one another. America is itself a sort of utopian community and this novel really works through all the problems orbiting around that.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. I read this novel against the interpretation offered by its author, who was in fact a terrible critic of his own work. Gatsby documents the moment when America went from being a rural and WASPish country to becoming a teeming, thriving urban and industrialized place where people’s family connections and inherited status counted for less and less. It’s suffused with anxiety about race and class mixing and the new economy that allows for all that.

It’s the Great American Novel of creative destruction, and despite being almost a hundred years old, it still describes our world today. In my reading, the hero of the book is Meyer Wolfsheim, the Jewish bootlegger who is described in some of the most anti-Semitic prose in American letters. The villain is the prissy Nick Carraway, who retreats back to a pre-modern America, “where dwellings are still called through decades by a family’s name.”

The Great Gatsby . . . It’s the Great American Novel of creative destruction, and despite being almost a hundred years old, it still describes our world today.

—Nick Gillespie

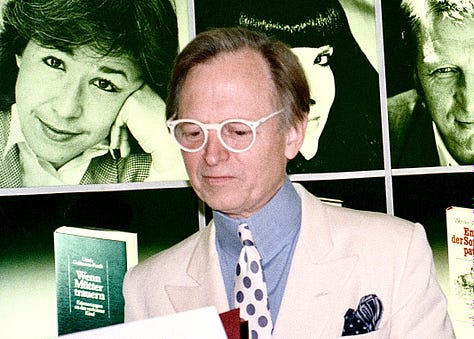

“The ‘Me’ Decade and The Third Great Awakening,” by Tom Wolfe. Published in New York magazine in 1976 (the Bicentennial Year!) by the great theorist and practitioner of “The New Journalism,” this essay captures perfectly how the United States belatedly delivered on its promise to be a new Eden, where all us could become American Adams and Eves, this time ostensibly without shame. Sometime after World War II, we stopped being a relatively poor country and became a fantastically wealthy one, in which all of us started acting as if we had the right to live like only the rich used to.

Wolfe is not uncritical of this (and we should be attentive to the costs and benefits too), but he’s also not terrified of it, as many people are. “The new alchemical dream is,” reads the subtitle, “changing one’s personality—remaking, remodeling, elevating, and polishing one’s very self.” That can be exceptionally liberating, especially for those of us who come from, say, the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution.

Just Kids, by Patti Smith. Anybody who grows up in New Jersey (as I did) grows up with an intense urge to be elsewhere and Patti Smith’s memoir of moving to New York from South Jersey in the late 1960s and finding her tribe, her muse, and her vocation as a punk poet–cum–rock god is a beautiful evocation of what it means to be an American—like Ben Franklin showing up in the big city, broke and with zero connections but plenty of ambition (the run-on is intentional).

Unlike Franklin, she shows up in the Big Apple just as it’s hitting the skids, but her account of meeting the beautiful, doomed Robert Mapplethorpe and building a world out of the rubble of the East Village is almost too beautiful and painful to experience even vicariously.

This book is of a piece with Bob Dylan’s Chronicles: Volume One and Bruce Springsteen’s Born To Run. In some profound way, rock stars represent to me the ultimate expression of American self-determination and self-creation. Many rock-star memoirs are sad affairs aimed at self-promotion and score settling, but each of these books details in very different ways how unique, larger-than-life characters created who they are through a mix of ambition, luck, and hard work. They are the children of Ben Franklin, as are we all.

I’ve heard you say that we’re all living in Philip K. Dick’s imagination now. He died in 1982. What did the sci-fi great foresee about our world?

I assume everyone knows that Dick is the inspiration behind movies such as Bladerunner (based on his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) and Total Recall (based on his short story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale”) and the TV series The Man in the High Castle (an elaboration of his novel of the same name); run, don’t walk, to read the novel A Scanner Darkly and the great Richard Linklater movie version of the same.

To me, Dick is the reincarnation of Edgar Allan Poe in that his protagonists are always first and foremost wondering if they are batshit crazy or maybe being dreamed by someone else. Poe himself is channeling Rene Descartes, who in the Cogito fears that we are not in fact the authors of our own consciousness, much less our own lives. This, I think, is the defining psychological condition of modernity. We’ve figured out enough about the world to hypothesize ultra-deterministic systems (of biology, say, or economics, or psychology) that give us the illusion of choice and free well. We suffer from imposter syndrome on an epistemological level.

The results in Dick’s works are simultaneously very funny and deeply worrying. I love Dick’s scenarios because you never know what is real and what is fantasy, often drug-induced. But sometimes the “simulations” are so ridiculous, you just have to laugh.

It’s weird enough that Ronald Reagan, who starred in the Bonzo movies with a scene-stealing chimp, became a major political figure. But when Arnold Schwarzenegger, who starred in Total Recall, becomes governor of California, and his conservative supporters immediately start calling for a constitutional amendment to let a foreigner become president, I was like, Okay, are we living in a Phil Dick novel in which a bodybuilder who is the son of Nazis first becomes a movie star and then the leader of the biggest state in the country?

Flow my tears, man! It’s Dick novels all the way down! I mean, what else can you think when you read stories about baseball bad boy Jose Canseco being pulled over with “diapered goats” in his car, or “the strange case of Fetus-Free Pepsi, the creation of an online dating service built around Atlas Shrugged, [and] the al Qaeda plot to kidnap the star of Cinderella Man”?

We suffer from imposter syndrome on an epistemological level.

—Nick Gillespie

Saying we’re living in a Philip K. Dick novel is shorthand for just how fucking weird our world is, and how much weirder it continues to get on a daily basis. What writer could have created Hunter Biden, or Lauren Boebert, or Elon Musk? The idea that Arnold would emerge as a major political player is strange—until you get to Trump. Or Zelenskyy (a comedian who played a president on a sitcom and then . . . becomes a surprisingly effective wartime president). I’m barely scratching the surface here, right?

Back in 1961, Philip Roth famously wrote, “We now live in an age in which the imagination of the novelist lies helpless before what he knows he will read in tomorrow morning’s newspaper.” He really had no idea just how strange the world was becoming. Dick, whose first novel would be published a year later, did. He was certifiably insane, often funny, and sometimes bitter and vindictive, but he really is the spirit animal of our world.

In the middle twentieth century there seemed to be a generally held liberal consensus about free speech, one that privileged the printed page. And while censorship has always been an issue, it seems like the trend toward book banning from both right and left has ramped up in the last few years. How do you—and maybe how should we—think about this wet-blanket moment?

First, we need to recognize it’s not a moment. It’s a reversion to the normal state of affairs in which some ruling elite believes it has not simply the right but the duty to filter what the rest of us consume. This is where an understanding of history and literature and philosophy is really helpful.

The Bill of Rights obviously starts with the First Amendment, but it really wasn’t until the late 1950s and 1960s that we enjoyed something approaching free expression, where you didn’t have to worry about getting arrested for publishing the wrong book or photos. I was born in 1963 and grew up in the seventies and eighties and simply took for granted that the free speech consensus of that era was the way things always were and always will be.

It became easier still in the 1990s for us to produce and consume culture and expression on whatever terms we wanted. But for the entire twenty-first century, that has been under attack in the name of state security, of decency, of antiracism/sexism/homophobia, of antitrust, policing medical or electoral “disinformation,” you name it. These days even the ACLU doesn’t take free speech as its highest value.

There’s a lot to be said about all of this. Some censors are pretty uncomplicated in their motivations—they just want power and control for a variety of economic, political, or psychological reasons. Others are, I think, well-meaning but misguided. The latter tend to believe in what Joli Jensen called an “instrumentalist” view of culture in the great book, Is Art Good for Us? These people tend to think that art and expression are like injectable medicines that make us sick or well, so you need to police them.

Jensen juxtaposes that to an “expressive” view of culture, one that holds art and related things are ongoing conversations in which we all participate and hash out who we are, what communities we belong to, and that sort of thing. The instrumentalist view implies a guardian class that must protect us from bad words, images, etc. We need to make visible that sort of presumption and show how elitist and misguided it is.

And we need to confront attempts to control business models in the name of free speech (this is ultimately what Net Neutrality was about). And we especially need to understand that any old-school distinction between the government and the private sector doesn’t exist anymore. The Twitter Files and Facebook Files show deep interpenetration in that regard. I highly recommend reading Jacob Siegel’s piece on how the concept of “disinformation” jumped from military intelligence to a truly pernicious way of framing free-speech battles online.

You were editor-in-chief of Reason magazine from 2000 to 2008 and then launched the magazine’s video channel after that. What motivates you as a writer and journalist?

I’ve been a journalist for my entire professional life. As an undergrad at Rutgers, I worked on the daily newspaper there (The Targum), mostly doing entertainment stuff: book reviews, music, things like that. There was a time when I wanted to be a novelist but ultimately I wasn’t that motivated (or talented) and, as I was finishing my doctorate, I applied for a job at Reason, which I’d been reading since sometime in high school. It allowed me (and still allows me) to comment on things I care about and do a deeper dive than I would be allowed to at most journalistic outlets.

I’m fascinated by the world, by the march of something like increasing amounts of autonomy to create and live in the world you want to, to create the self, things like that. I’m also very interested in figuring out what sorts of systems are more conducive to those types of societies.

All four of my grandparents were peasants who emigrated from Ireland and Italy in the 1910s, getting here just before the gates slammed shut for forty years. For a thousand years my ancestors were subsistence farmers and laborers. I’m one generation removed from the slums, especially on my father’s side (he was born in Hell’s Kitchen in the twenties and never graduated high school), and I’m amazed at the broad increase in wealth and freedom that has taken place globally over the last hundred years or so.

None of this is perfectly distributed or secure, but in 2018 the Brookings Institution announced that for the first time in human history a majority of people on the planet were middle class or wealthier. How did that happen? How do we keep it going and expand it? How do we create not just a country but a world in which more people are free to create themselves? Those are the big questions that energize me. On a less-grandiose scale, how do we create a more free, more fun, more fair world for my kids and everyone else’s? What are the attitudes, the policies, the communities, and traditions we need for that?

How do we create a more free, more fun, more fair world for my kids and everyone else’s? What are the attitudes, the policies, the communities, and traditions we need for that?

—Nick Gillespie

“We are as gods and might as well get good at it,” Stewart Brand wrote in The Whole Earth Catalog. By producing a wealthier, more peaceful world, we’ve pushed more and more of us up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. We’ve massified existential angst, but we haven’t yet given people the tools to deal with that. It’s hard work, unending work to create meaning everyday.

You’ve been highly productive over the years. A couple of books, plus countless articles, reviews, interviews, and podcast episodes. Describe your work process. How do you get it all done, week after week?

Thanks for saying that. I really feel like I’m finishing maybe 25 or 50 percent max of what I set out to do. One benefit of being the child of two parents who grew up poor and expected to be poor their whole lives is that I inherited a dread sense that every day is the day I get fired. That’s pretty motivating, to be honest, though it also makes it hard to enjoy time off. I grew up lower middle class with a palpable sense that everything I had could easily disappear and that the big difference maker for me was going to be work effort, not brains per se.

And again, there’s Ben Franklin and all his figurative sons and daughters to learn from: make a schedule, write it down, try to stick to it. Not early to bed, early to rise necessarily, but an appreciation for grinding it out.

Over the thirty years I’ve been at Reason, I’ve changed my job here on a regular basis, which also keeps things fresh. I sometimes take for granted that my work is an expression of my fundamental commitments, but it’s a real blessing and motivator to keep going and growing.

As a writer, what do you find to be the greatest challenge in (a) starting and (b) completing a project? What’s the one project you’ve been procrastinating the longest?

I overthink things way too much and build up everything I’m about to do to a point where it’s almost insane to even start. Starting is much harder for me than completing something—or (same thing) declaring something is done. One benefit of being a journalist is that you have to keep cranking. Perfection doesn’t exist, so get something to a good-enough level and send it out to the world. I believe in iteration, not perfection.

I played a lot of baseball as a kid and one thing I took away is an appreciation for trying to improve your average over the course of a season. Each at-bat is relatively insignificant, but are you picking up more hits over time? Whatever I’m doing doesn’t have to be great, but it should be better than the last swing—that sort of thinking.

I almost put Bernard Malamud’s The Natural in the section about novels and America. It’s a great allegory about a country that can easily spoil its promise by refusing to work hard to realize its potential. I take from that novel (not the terrible, bowdlerized movie that changed the ending) the realization that there is not one big home run or single victory that changes everything. You’ve got to keep stepping up to the plate and taking your best swings, knowing most of the time you will fail.

I’ve been procrastinating on so many projects, I don’t know where to begin. When I was a manager of writers and video producers at Reason, I used to tell people that the measure of success isn’t really whether you hit all the goals on your to-do list but how much and how good the things were that you did. Benchmark yourself against what you actually did, not what you hoped to do. I struggle to think of my own efforts that way, but I think it’s the way we should measure ourselves.

Benchmark yourself against what you actually did, not what you hoped to do.

—Nick Gillespie

Final question: You can invite any three authors, living or dead, for a lengthy meal and conversation. Language is no obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

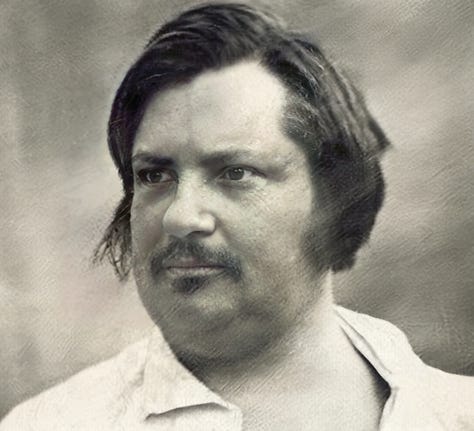

Balzac, Tom Wolfe, Camille Paglia. I’ve only read Balzac in translation, and I realize his attitudes toward capitalism, democracy, and modernity were complex and a mix of regressive and progressive, but his novels tell the thick history of the world we still live in, one characterized by the liberating aspects of bourgeois capitalism that Marx and Engels lauded in the early pages of The Communist Manifesto.

He depicted everything solid dissolving into air and mapped all the good, bad, and indifferent outcomes related to that. I would love to ask him too about why he invented an aristocratic pedigree for himself the minute he could. The psychology of his characters, whether male or female, established or arriviste, rising or falling, is intriguing and unsurpassed in fiction.

I reviewed Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities for a small magazine when it came out and he of course praised novelists like Balzac and did something similar in that book and most of his reported nonfiction through the late 1980s—he wrote a thick social history. He too had a bullshit degree(!)—a PhD in American Studies, I believe—and put it to fantastic use in a field that was dying for the sorts of insights such a framework could provide.

His interest in and love for American subcultures still energizes me. When Philip Roth was complaining that America was becoming too crazy to write about, Wolfe hit the road and talked with the Merry Pranksters and hot-rodders and everyone else and helped journalists become more important than novelists. (I recommend the new documentary about him, by the way, Radical Wolfe.) His willingness to talk about class and status and their shifting meanings is central to how I think about the world even as I disagree with many of his particular insights or declarations.

I’ve had the privilege of interviewing Camille Paglia a couple of times for Reason and she is first and foremost a fantastic talker. Though she never studied with Leslie Fiedler, she rarely misses an opportunity to acknowledge her debt to him and it shows on every page she writes. I love the way she mixes high and low and goes straight to the heart of what she cares about; yes, Madonna (the singer) is a major cultural force!

She grew up Italian American and blue collar in upstate New York and her passion for the promise of America is infectious and borne out of personal experience that I can relate to; she’s like a long-lost cousin who helps me understand the world using the family pidgin. At the same time, as a lesbian and outsider for a ton of other reasons too, she brings a different approach to everything she discusses. I think she’s getting a little stuffy in some of her interpretations, but her love of literature and its power to inspire is exactly what’s missing from academic discussions of the same.

Needless to say, I wouldn’t get a word in edgewise, but I’d happily pick up the check.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts: