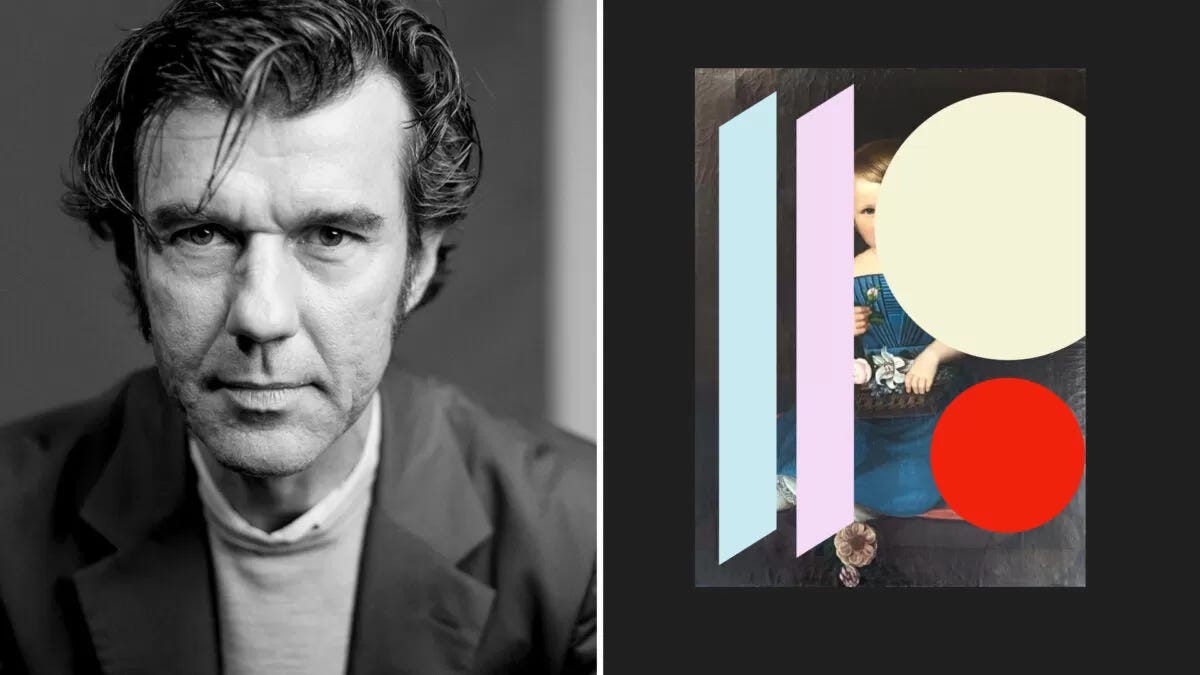

Stefan Sagmeister: An artist who believes 'Now Is Better'

The legendary designer's new show uses the work of Our World in Data, Human Progress, and Steven Pinker to document material and moral progress over the past few centuries.

I’m very happy to share my latest Reason video interview with you. It’s with Stefan Sagmeister, a design legend who has a fantastic new exhibition at Patrick Parrish gallery in Soho through June 6. If' you’re in New York City, definitely go check it out.

Here’s a 20-minute video that I produced for Reason with Kevin Alexander and a RUSH, UNCORRECTED transcript of the video. CHECK ALL QUOTES AGAINST THE AUDIO. There’s also an hour-long podcast version that you can listen to here or at the bottom of the page as a Spotify stream. Stefan is one of the most interesting people I’ve talked to in a long time—his cautious optimism is extremely attractive and his career is wide-ranging and fascinating. I also really dig his pro-New York City and America vibes.

If you care about art, commerce, progress, and “factful” approaches to life exemplified by the websites Our World in Data and Human Progress and intellectuals such as Steven Pinker, this is right up your alley. If you’re a pessimist, this will challenge your gloom.

Without further ado:

RUSH TRANSCRIPT—UNCORRECTED—CHECK ALL QUOTES AGAINST AUDIO/VIDEO.

SPEAKERS

Nick Gillespie, Stefan Sagmeister

Nick Gillespie 00:04

Is the world getting better? Or is it on the verge of collapse? Stefan Sagmeister emphatically believes that things are looking up and in the art exhibition now is better, showcases a bold new way to convince the world that he's right. He takes actual paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries disassembles them and creates new works by juxtaposing them with data visualizations of just how much things have improved since the good old days. Some works chart the incredible decline over the centuries and deaths on the battlefield from famine, and from extreme weather events, while others show how much cheaper food and lighting have become in real terms. One Piece documents the explosion in the number of guitars per person on the planet is an indicator of growth and leisure and entertainment, while another charts the persistent belief that crime is always rising, despite its well documented decline, a heralded graphic designer who is designed to album covers for Jay Z, The Rolling Stones, and Lou Reed. He's won two Grammy Awards, including one for his design of the talking heads boxset, once in a lifetime, born in Austria in 1962. He's called New York City home since the 1990s. And he draws on sources such as our world in data, human progress. And the work of Steven Pinker, who has written the foreword to an art book of the Now Is Better series that's due out later this year, in a wide range of conversation, Sagmeister tells me why it's so important to acknowledge and defend material progress, why art and commerce are not enemies, and what he loves about the new world he's adopted as his homeland. And how that ties in to the now is better project.

Nick Gillespie 01:51

Stefan Sagmeister, thanks for talking to reason.

Stefan Sagmeister 01:53

Wonderful, thank you so much.

Nick Gillespie 01:55

So give me the elevator pitch on the now is better show? Well, it's

Stefan Sagmeister 02:00

basically comes out of my interest in long term thinking. Because I discovered that there are really two ways to look at the world. One is from a very short term perspective, what is happening right now, which is basically with all media looks at it. And if you do that, almost by definition, everything looks bad, because things that are going bad, go bad quickly, scandals, catastrophes, and so on. While many things that develop well, that develop positively do so very slowly and don't really work, you know, through a news cycle. But that's really what the show is about, to look at the world from long term perspective. 20 years, 50 years, 200 years, I think we have a couple of pieces that are 500 years. And bear if you take that point of view, many, many things look very positive.

Nick Gillespie 03:04

Was there a moment where you were like, Aha, this is, this is what my work is going to be for the next few years or loss, what house now,

Stefan Sagmeister 03:14

I was lucky enough to get one of those residencies at the American Academy in Rome. And one evening, I was sitting next to a lawyer who was the husband of one of the residents, artists. And he told me that what we see in Poland, in Hungary in Brazil, at the time, really means the end of modern democracy. He was a highly educated person. And I looked it up, I went back to the studio that night and quickly Googled it. What's the story of us modern democracy? When did it start? And if you went back 200 years, there really was only one United States. I went back 100 years after World War One. They were I think, 18. And now we have just a good ad, I think 87 democracies, that the UN says they're democracies. So it turned out that this smart man had really no idea of the road that he lives in. But I discussed it with other people, and was immediately surprised how much pushback I would get. Because, you know, specifically, there were certain people that in this case, it was mostly on the political left, who somehow want to believe that things are going down, that there is some sort of an investment in that. What do you think that is? I think if you're an activist, it might be easier to get people over to your cause if you can tell them how bad things are. And I think there's a truth to that. Many of us being so overwhelmed by all the negative news that we get on a daily basis, give up and say, Oh, this is so terrible. We can do anything anyway.

Nick Gillespie 04:59

You One of the paintings that you have is titled richer and poor. And it shows in 20 29% of the global population was living in poverty, compared to in 1990 35% of the global population was living in poverty. But then you ask how many people believe poverty has gotten worse, and 55% of people believe that poverty has gotten worse over the past 30 years? Only 12% believe that it's gotten better, which it has. So are people misinformed? Or do they want to believe that they're living in a bad period?

Stefan Sagmeister 05:36

I think it's a mix. I think it's a it's a mix of I don't believe that the media is inherently evil, or,

Nick Gillespie 05:46

or is trying to mislead people. No, they believe what they're saying they believe

Stefan Sagmeister 05:50

what they're saying. And they know, specifically now, in the last 20 years, since we have clickable links, they know what people like. And the media gives us what we like. And we all prefer negative news over positive news, I am just like everybody else, I also do prefer negativity. And I actually think to create pieces that are positive, is somewhat more challenging. Because they by themselves, tend to be less interesting, the vast majority of pieces when they have anything to do with commentary of life, social commentary, anything will be critical, or negative

Nick Gillespie 06:41

one of the series of pieces in the collection, look at how much richer we are, one actually looks at global GDP and how much richer the planet is not fascinating. One painting is bright lights, time worked for an hour of light and an 1800. That was six hours of work for an hour of light in 2000 was two seconds, work for an hour of light, you have another one about the hours working a job. And it's amazing that not only has the amount of work you have to do for a second of light has come down. But the amount that we work is much less how do people respond when you say, well, actually, you're working a lot less than your your father probably are your grandparents.

Stefan Sagmeister 07:27

On the work front, I think there is an interesting phenomena going on right now in France, you know, where you have all these protests going on? Against moving the pension years up? Yeah. And I think that's a direct result of this information not being part of our daily discussion. Because if everybody would be aware that we now live double the amount of time than we did 100 years ago, then it's just logical that we would have to work a little bit more before we can go into our retirement.

Nick Gillespie 08:12

You have a piece called artists, lawyers, and doctors, and this is the number of artists, lawyers and doctors in the US artists 2.5 million lawyers, 1.3 million doctors 900,000 Is it a sign of a good society that there are more artists than doctors,

Stefan Sagmeister 08:29

it's definitely the sign of a good society, that it would be able to sustain a very large group of people that has very little function, we can do anything before we'd have shelter before we can't breathe, and eat. And so all of these other things, and specifically, the artistic impetus is only be able to even to be presumed once we have shelter, and once we are

Nick Gillespie 09:00

paved paintings are of the animals that hunters caught. So exactly. You you can pay it after you've eaten, but probably not before,

Stefan Sagmeister 09:08

and they're done in a cave once you are shelter,

Nick Gillespie 09:11

right? Yeah, yeah. And you have another piece, the number of playable guitars in the world, which is increased massively. So that speaks to the idea that it's a pretty good world where a lot of people are expressing themselves creatively. That's an indicator that we're doing pretty well.

Stefan Sagmeister 09:28

Yes, the numbers Mr. Guitars is absolutely astonishing, because it went from a couple of hundreds decades ago to 10s of 1000s right now, so it meaning the increase is just incredible.

Nick Gillespie 09:43

going in the other direction. You have a painting that talks about the decline in the number of deaths from natural disasters, which is also something that again, if you're, I would say if you're over 40 You should have no problem realizing like when you were younger, you would hear all of these stories about, you know, hundreds of 1000s of people starving to death or dying because of earthquakes or volcanic eruption or tidal waves. And you don't really hear that very much anymore. But we think the world is getting worse on that scale as

Stefan Sagmeister 10:15

well. It's exactly what we talked about in the beginning is that there has never been a news report about, there was no earthquake in California today. So all the positive, things just go unreported. But even the absolute number of people dying went down

Nick Gillespie 10:35

as a fraction of what it used to be. And that's certainly true of things like pandemics and whatnot. So however bad COVID was, the response was quicker and more effective than the 1918 flu epidemics.

Stefan Sagmeister 10:47

I always found it fascinating that doing COVID, one of the routes that was used the most in the media also in the New York Times was unprecedented, right? Even though the people who wrote that clearly had the knowledge that this is not unprecedented, maybe unprecedented this year, but for sure, not unprecedented this century, where you had AIDS that killed 30 million people. You had the Spanish flu was between 50 and 100 million people. And so you know,

Nick Gillespie 11:19

a number of the pieces talk about immigrants and immigration being a positive thing. You yourself are an immigrant from Austria to New York, you first came here in the late 80s. You settled here fully in the early 90s. What drew you to New York? And how does that reflect in your work?

Stefan Sagmeister 11:38

Well, I came here first, right off the high school, it was a high school gift from my brother in law, it was in 81. So New York was from its now perspective, in a pretty bad shape. I would say crime was incredibly high. But it was just fascinating to me. Even though I was born in a very pretty small town in Austria, I was always attracted by big places. I think it's also a lovely mix of American friendliness, which might be odd, because you know, your New York is not exactly, but ultimately, it is quite open. And I haven't done a piece with it yet. But I've just come across and I checked it. And it seems to hold up, I just came across data that shows that refugees not immigrants, refugees, that have been in this country for 25 years or longer, have a 30% higher income than the average American and with immigrants, okay, I believe that by the refugees is pretty astonishing that refugees in their lifetime, not in the beginning when they come around, but in their lifetime would surpass the locals, I find that to be the strongest indicator that there is an American Dream that that is alive that I've come across. And I know it has been incredibly fashionable to say that the American Dream is dead. And even I feel sort of like a silly sitting here are claiming otherwise. But those numbers point in that direction.

Nick Gillespie 13:19

Your background is as a graphic designer, which is more functional than mere, you know, then art right then full mental. Do you see a sharp distinction that many artists are going to critics would draw between kind of commercial art or instrumental art and real art? Is that a false dichotomy?

Stefan Sagmeister 13:39

I can argue it both ways. If people ask me, what do you call yourself, I definitely am a designer. And the work that I'm doing here, I would also see as design work, simply because I would say that there is a functionality to it, and which I find pleasing. But I also totally understand that many artists would not want any functionality to their pieces.

Nick Gillespie 14:07

That's the whole point of art, right is that it resists being used for some other purpose

Stefan Sagmeister 14:12

and I would say be even dare would have to really say it's the whole point of contemporary arts, because out by itself, if you look at his historically, of course, also has many functions, right? Many of the most famous artists in the past did very functional versus, you know, Michelangelo designed candlestick holders layer now, though, obviously, there are many, many other things. There is no such thing as pure functionality. It's all on a scale.

Nick Gillespie 14:43

Talk a little bit about your process for the pieces in this exhibition. Basically, you buy cheap paintings from the 18th and 19th century and you put data visualizations over that

Stefan Sagmeister 14:56

it originally started with pieces that we still had In the attic in the house that I grew up with, that came from my great, great grandfather's store who was an antique dealer in Western Australia, and the stuff that didn't sell bound up still being stored there to this very day. So the first pieces really came from there. Yeah. And since then, by now, I think connected to about 30 auction houses, all of them in Central Europe, mostly Austria's. But so what do you pay your money?

Nick Gillespie 15:28

What do you pay for a piece that you're going to paint over?

Stefan Sagmeister 15:31

I think they're all for sure. Under 4000 euros, which, you know, I'm kind of a beneficiary of the fact that specifically 19th century art, but also 18th century art is very much out of fashion right now,

Nick Gillespie 15:49

what is the pleasure of painting over, you know, a piece from the early 19th century, with a data visualization that shows how much better things have gotten,

Stefan Sagmeister 15:59

but we are not really painting over, we are really basically taking the piece apart, we are plucking holes into it. And we are inserting the new data. So the peace if you want this destroyed, which I had given some thoughts about, meaning ultimately, I solved it for myself thinking that if somebody in 200 years takes my work that they found at Tiny auction houses and makes a new piece out of it, I think I would be very happy about it. But the process really is I buy these pieces at auction, by then I've already had received the photo. So I ultimately try out designs. And these can be inspired by the data, they can be inspired by a color scheme, they can be inspired by form, they can be inspired by a composition, they can be a reaction on the existing piece. But ultimately, by and large, I'm trying to go against the composition that is existing, because that sort of seems to create the kind of tension that ultimately makes a good Lu composition.

Nick Gillespie 17:21

How much did you increase? On average? Just make it up? If you have to, you know, if the average painting that you started with cost 4000 euros? What was the average that you were selling it for? How much did you increase the value,

Stefan Sagmeister 17:35

I think it's probably times two or three. But of course, there's also significant cost involved in creating this, you know, like there is an incredible amount of just hours that go into that not just myself or from my own. But there's a whole team working on this in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, there is costs in the renting the space and all of that stuff. So there is that. But ultimately, I actually try to keep the price as low as it's possible that it still make sense. I want this to be in as many homes as possible. That's the functionality of it. Because ultimately the goal and in therefore really, it's embedded in the concept that these things hang on somebody's wall, as a reminder that what they just read on Twitter doesn't mean it's the end of the world.

Nick Gillespie 18:29

You've worked with a number of very globally known recording artists like Lou Reed like the talking heads, like The Rolling Stones, and you did an album cover for the Rolling Stones, which album was out again, but just about everyone. Yeah. So you know, that's like a platinum record. What what does it feel like to know that your images are going out to you know, a million people or more fantastic, you

Stefan Sagmeister 18:53

know, it's also something that I love about design is that it's a pretty democratic way of working where you know, we do the cheesy cover where the first print run was 5 million for the price of 20 $25. Yeah. Which I don't think there is a publication in the art world that reaches those kinds of numbers. I very much love the fact that design tends to live within our lives. I see myself as a communication designer, more so than a graphic designer. I think the challenge specifically for somebody like me is to make these things interesting enough that even though they're positive, people will be engaged. And you know, that's the challenge.

[end]

Here’s the longer conversation, as a podcast: