My old man was a baseball nut who lived in New York City during that great golden era of Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, and Duke Snider each playing centerfield for the Giants, Yankees, and Dodgers. You just couldn't believe it was real, he told me, all that talent, all in the same city!

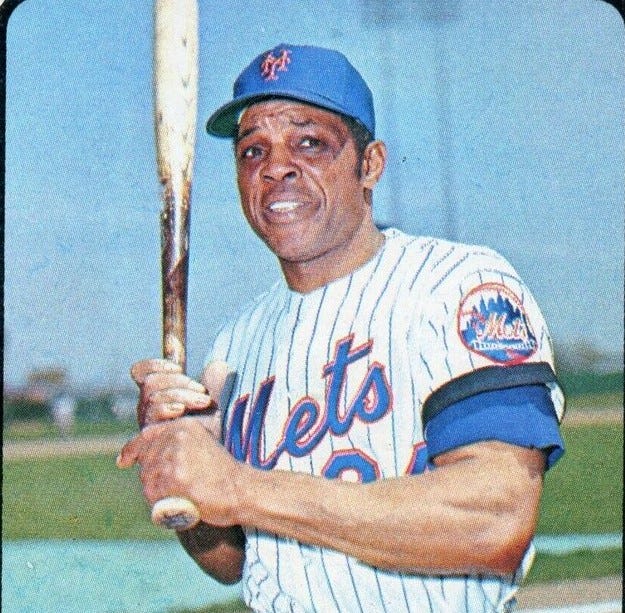

In 1973, when I was about 10, he took me to see the Say Hey Kid play in the flesh. Mays was finishing out his career in desultory fashion with the Mets, an impossibly old throwback at the advanced age of 43. Like Hank Aaron, another aging great whose career had started in the 1950s and was winding down, Mays had started out in the Negro Leagues, whose very existence was utterly unfathomable to a kid watching ball in the ‘70s and whose favorite players were as likely to be black as white. In my head, Mays was like the NFL’s Johnny Unitas, another guy whose career stretched from the 1950s into the modern day (or, more precisely, my modern day). They were not just from a different era, but from a different planet.

By the early ‘70s, Little League was starting to use aluminum bats and major leaguers were growing facial hair that made rock stars look square. The American League adopted the DH rule in ‘73. Ted Williams—whose greatness at hitting and fly-fishing my father would extol on a regular basis—put his signature on all the equipment in the sports department of Sears, which I already understood was a fading ember from a very different America. How could Ted Williams have been any good, I remembered thinking, if he has to endorse all this Sears crap?

Though a Dodgers diehard, my father said Mays was the best player of all time, even better than Babe Ruth, whom he'd seen as a kid in his final season with the Boston Braves (1935). He loved the stories of Mays playing stickball with New York City kids on his days off.

Now you're going to see a great ballplayer, he said as we settled into the cheap seats at Shea and proceeded to watch Mays whiff, drop balls, and run stiff-legged. (He would finish the season with a career-low batting average of .211).

This is embarrasing, Dad, I said, smug in my stupid-kid arrogance that anything from before my time was useless and obsolete and lame. I probably added that Mays wasn't even up to the level of a Don Hahn or George 'the Stork' Theodore.

You know, you're not always going to young, he said, laughing off my analysis. And you don't know very much about baseball.

He was right on both counts, of course. But I wonder if he wasn’t contemplating his own life--he turned 50 that year and grew up in a world where that was old--and what he'd done to have such a jerk kid who couldn't appreciate the past. A World War II vet who never finished high school, he knew his generation's time was passing, yielding to a world that was infinitely better than the one he grew up but that he didn't really understand.

As I got older and learned more about baseball, I of course realized how amazing Mays had been, especially on top of the extra pressures he faced due to his race. He came up to the Majors in 1951, just four years after Jackie Robinson had broken the color line and four years before the Yankees would integrate their squad. The Giants move to the West Coast, where he didn’t quite fit in, and his personal life added tensions too. (Leo Durocher's Nice Guys Finish Last is a powerful read about Mays in his NYC heyday). I always felt embarrassed whenever I saw Mays because it reminded me of a time when my father tried to share something with me and I didn't even understand the gesture, much less accept it with grace. Such is youth.

Robinson called Mays out in his incredible oral history Baseball Has Done It for not speaking up on civil rights and that's a legit critique as far as it goes (I know my old man took it hard when fellow veteran Robinson died in 1972, at just 53 years old).

But for nearly a quarter of a century, Mays held court in centerfield and inspired thousands (millions?) of kids with his play and unbridled love of the game. He also inspired older fans who could remember their youth and dreams reflected through his career, his energy, and a still basically unrivaled highlight reel. He still does, and will for years to come.

Willie Mays, RIP.

My Willie Mays story: It must have been 1969 or 1970 and I would have been 8 or 9. We went to see the Giants play the Phillies at Connie Mack Stadium (a complete dump that nobody who actually remembers it misses). We got there early, and I remember two things about the game, both from before it started.

We saw Willie in batting practice and he hit one OVER the left field bleachers. Maybe it landed on the roof, but it was impressive.

A little later he came to the stands just beyond first base to sign autographs. A mob of little boys fought amongst themselves to get to the front. We were too far away, although I was very jealous of the kids who were there. An old fart security guy came over to shoo the kids away and Willie chewed him out. The guard slunk away and Willie went on signing.

Late 50s through late 60s life was a blast in so many ways, and baseball fit in perfectly to the American lifestyle. I miss those days, or at least the memories. I was an aerospace engineer because of the hot times of the space race. It’s hard to believe all the great Americans from that period, and Mays personified to can-do attitude of the period…